Problem Solving

Adapted in part from from Dumper, Jenkins, Lacombe, Lovett, & Perimutter. Problem-Solving. In Openstax Psychology. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

Learning objectives

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

Introduction

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe, for example, you typically need only double each ingredient in the recipe. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

Problem-solving strategies

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as well-defined and ill-defined problems (Pretz et al., 2003). Well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions; Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates logical reasoning and requires abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding (also known as problem analysis), problem shaping (where the organization of the problem occurs), generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (see, e.g., the table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Problem-Solving Strategies

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trial and error | Continue trying different solutions until problem is solved | Restarting phone, turning off WiFi, turning off bluetooth in order to determine why your phone is malfunctioning |

| Algorithm | Step-by-step problem-solving formula | Instruction manual for assembling some Ikea furniture |

| Heuristic | General problem-solving framework | Working backwards; breaking a task into steps |

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Sternberg & Ben-Zeev, 2001). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is yet another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts (or “rules of thumb”) that are used to solve problems. Such rules cam save time and energy when making a decision, but are not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. For example, imagine you live in College Park MD and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that I-95 traffic is a thing even on Saturdays, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes about 2 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even realizing it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often take this approach to complete a large research project or long paper. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

There are at least two ways to break problems into smaller parts. One is to take whatever next step moves you closer to your goal – this is termed the hill-climbing heuristic. So, for example, if your goal is to make a lot of money, you might take a job right out of high school, thus making more money than your college-bound friends. The hill-climbing heuristic can work well, but as you can imagine from this example, it can sometimes backfire (e.g., when your friend’s fancy Psychology degree lands them a lucrative position at, uh… let’s say Google or something). A related approach is the means-ends heuristic, where you identify the “ends” (final result) for various subproblems (~steps along the way to your goal) and then figure out the “means” (or methods) you will use to reach those ends. Two classic examples of means-end analysis can be found in the River Crossing Problem and the Tower of Hanoi Problem

| River Crossing Problem |

|---|

| Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time. You can try an interactive version of this problem here. |

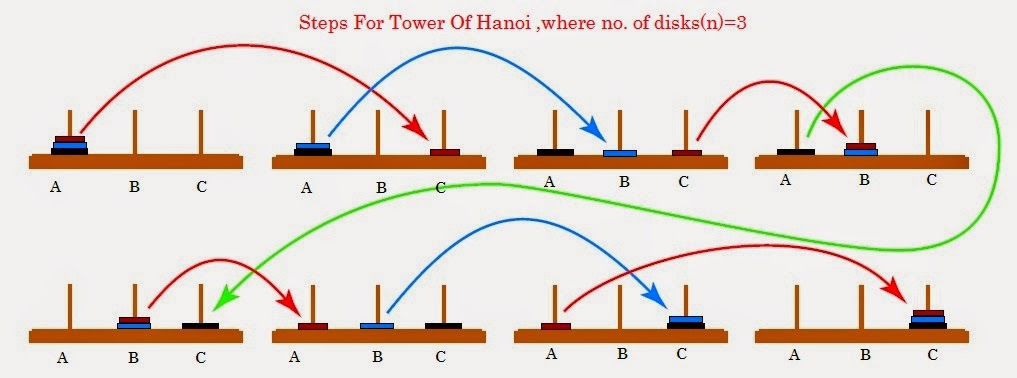

| Tower of Hanoi Problem |

|---|

| The Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules: 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time. 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod. 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk. |

With 3 disks, the puzzle can be solved in 7 moves:

The minimal moves required to solve a Tower of Hanoi puzzle is 2n – 1, where n is the number of disks. For example, if there were 14 disks in the tower, the minimum amount of moves that could be made to solve the puzzle would be 214 – 1 = 16,383 moves (OMG what a pain). There are various ways of approaching the Tower of Hanoi and related problems, so involves multiple aspects of problem solving (including understanding the problem and choosing appropriate strategies). Because of this, a variation of the Tower of Hanoi (the “Tower of London”) is used in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

If you figured out one of these problems via insights from the other problem’s solution, you were reasoning by analogy. This analogy heuristic is a useful approach to many real-world problems, and involves trying a solution that solves a similar problem. One challenge with the analogy approach is to apply solutions from problems that are actually analogous (even when quite different in their surface features)–so-called problem isomorphs–and not applying solutions from problems that appear similar on the surface (e.g., are about similar topics) when the underlying problem structure is actually quite different.

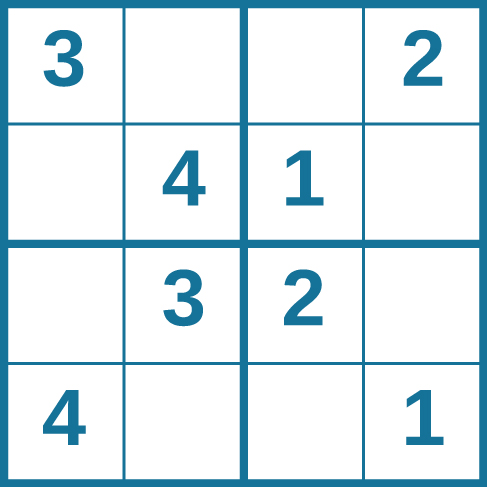

Solving puzzles

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. For example, sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid, but the simple sudoku to the right is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Try the one to the left if you like!

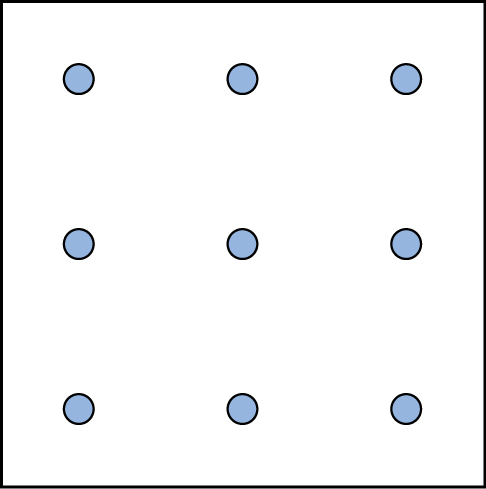

On the right is is another type of puzzle that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Can you connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper (or, uh… your stylus from the tablet)?

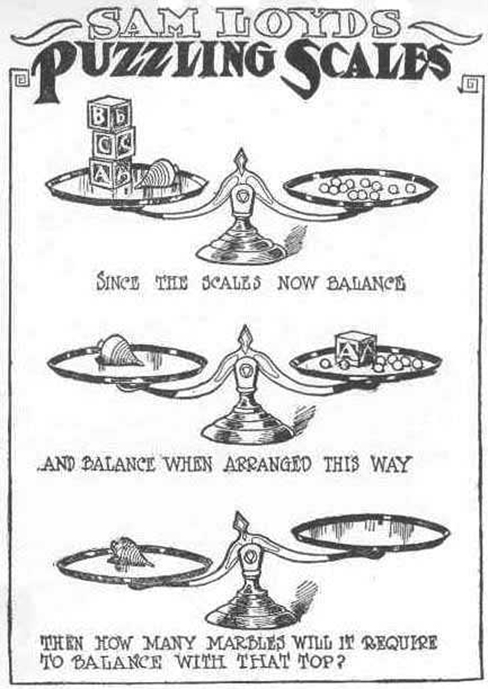

Now take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below. (This one is by Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, who created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime; Loyd, 1914).

Pitfalls in problem solving

Not all problems are successfully solved. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck, but she just needs to go to another doorway instead of trying to get out through the locked door. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you do not consider using something for a purpose other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

An example of trying to overcome functional fixedness in Apollo 13

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, German and Barrett (2005) asked if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. They asked individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador to solve problems that required using an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. Thus functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures.

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Sometimes we come up with unconventional, creative solutions. And sometimes we are swayed by biases and systematic errors. We’ll return to some of these issues in our next topics on creativity and on decision making.

(Did you want to see solutions to the puzzles above? You can find them here.)

Summary

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include mental sets (including functional fixedness), and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

Glossary:

- algorithm

- problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

- functional fixedness

- inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

- heuristic

- mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

- mental set

- continually using an old solution to a problem without results

- trial and error

- problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

- working backwards

- heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

References

- German, T. P., & Barrett, H. C. (2005). Functional fixedness in a technologically sparse culture. Psychological Science, 16(1), 1-5.

- Lloyd, S. (1914). Sam Lloyd’s Cyclopedia of Puzzles.

- Pratkanis, A. R. (1989). The cognitive representation of attitudes. Attitude structure and function, 3, 71-98.

- Pretz, J.E., Naples, A.J., Sternberg, R.J., Davidson, J.E., Sternberg, R.J. (2003). Recognizing, defining, and representing problems. The psychology of problem solving (pp. 3–30). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. & Ben-Zeev, T. (2001). Complex cognition: The psychology of human thought. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Adapted from

- 7.3 Problem-Solving by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett, and Marion Perimutter, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.