Speech perception and language use

Adapted from multiple sources (see below)

Human language is arguably the most complex behavior on the planet. Language involves both the ability to comprehend spoken and written words and to create communication in real time when we speak or write. Most languages are oral, generated through speaking. Speaking involves a variety of complex cognitive, social, and biological processes including operation of the vocal cords, and the coordination of breath with movements of the throat and mouth, and tongue. Other languages are sign languages, in which the communication is expressed by movements of the hands. The most commonly signed sign language is American Sign Language (ASL), currently used by nearly 3% of the adult population in the United States alone (Mitchell & Young, 2022).

Learning Objectives

- Define language and gain familiarity with the components of language

- Understand the challenges of speech perception

- Explain categorical perception and some top-down influences on speech perception

- Consider the relationship between language and thinking

Introduction

Language is used in our everyday lives. If psychology is a science of behavior, scientific investigation of language use must be one of the most central topics—this is because language use is ubiquitous. Every human group has a language and all typically developing human infants learn at least one language (and often multiple languages) without being taught explicitly. Even when children who don’t have much language to begin with are brought together, they can begin to develop and use their own language spontaneously with minimal input from adults. For example, in Nicaragua in the 1980s, deaf children who were separately raised in various locations were brought together to schools for the first time. Teachers tried to teach spoken Spanish and lipreading with little success. However, they began to notice that the children were using their hands and gestures, apparently to communicate with each other. Linguists were brought in to find out what was happening and it turned out the children had developed their own sign language by themselves. That was the birth of a new language, Nicaraguan Sign Language (Idioma de Señas de Nicaragua, or ISN; Kegl, Senghas & Coppola, 1999). Language is ubiquitous, and we humans may be born to use it.

Although language is often used for the transmission of information (“turn right at the next light and then go straight,” “Place tab A into slot B”), this is only one of its functions. Language also allows us to access existing knowledge, to draw conclusions, to set and accomplish goals, and to understand and communicate complex social relationships. Language plays an important role in our ability to think, and without it we would be nowhere near as intelligent as we are. And while language is a form of communication, not all communication is language. Many species communicate with one another through their postures, movements, odors, or vocalizations. This communication is crucial for species that need to interact and develop social relationships with their conspecifics. However, many people have asserted that it is language that makes humans unique among all of the animal species (Corballis & Suddendorf, 2007; Tomasello & Rakoczy, 2003).

Components of Language

Language can be conceptualized in terms of sounds, meaning, and the environmental factors that help us understand it. Phonemes are the elementary sounds of our language, morphemes are the smallest units of meaning in a language, syntax is the set of grammatical rules that control how words are put together, and pragmatics refers to the elements of communication that are not strictly part of the content of language but that help us understand its meaning (e.g., contextual information).

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that makes a meaningful difference in a language. The word bit has three phonemes, /b/, /i/, and /t/ (in transcription, phonemes are placed between slashes), and the word pit also has three: /p/, /i/, and /t/. In spoken languages, phonemes are produced by the positions and movements of the vocal tract, including our lips, teeth, tongue, vocal cords, and throat, whereas in sign languages phonemes are defined by the shapes and movement of the hands.

There are hundreds of unique phonemes that can be made by human speakers, but most languages only use a small subset of the possibilities. English contains about 45 phonemes, whereas other languages have as few as 15 and others more than 60. The Hawaiian language contains only about a dozen phonemes, including 5 vowels (a, e, i, o, and u) and 7 consonants (h, k, l, m, n, p, and w).

Whereas phonemes are the smallest units of sound in language, a morpheme is a string of one or more phonemes that makes up the smallest units of meaning in a language. Some morphemes, such as one-letter words like “I” and “a,” are also phonemes, but most morphemes are made up of combinations of phonemes. Some morphemes are prefixes and suffixes used to modify other words. For example, the syllable “re-” as in “rewrite” or “repay” means “to do again,” and the suffix “-est” as in “happiest” or “coolest” means “to the maximum.”

Syntax refers to the set of rules of a language by which we construct sentences. The syntax of the English language requires that each sentence have a noun and a verb, each of which may be modified by adjectives and adverbs. Some syntaxes make use of the order in which words appear, while others do not. In English, “The man bites the dog” is different from “The dog bites the man.” In German, however, only the article endings before the noun matter. Der Hund beisst den Mann means The dog bites the man, but so does Den Mann beisst der Hund.

Words do not possess fixed meanings but change their interpretation as a function of the context in which they are spoken. We use pragmatics, including the information surrounding language, to help us interpret it. Examples of pragmatically-relevant contextual information include the knowledge that we have and that we know that other people have (common ground), and nonverbal expressions such as facial expressions, postures, gestures, and tone of voice. Misunderstandings can easily arise if people aren’t attentive to such contextual information or if some of it is missing, such as it may be in newspaper headlines or in text messages.

We combine these different components of language in novel and creative ways, which allow us to communicate information about both concrete and abstract concepts. We can talk about our immediate and observable surroundings as well as the surface of unseen planets. We can share our innermost thoughts, our plans for the future, and debate the value of a college education. We can provide detailed instructions for cooking a meal, fixing a car, or building a fire. The flexibility that language provides to relay vastly different types of information is a property that makes language so distinct as a mode of communication among humans.

Speech perception

Speech perception is the process by which the sounds of language are heard, interpreted, and understood. The study of speech perception is closely linked to the fields of phonology and phonetics in linguistics and cognitive psychology and perception in psychology. Research in speech perception seeks to understand how human listeners recognize speech sounds and use this information to understand spoken language. Speech perception research has applications in building computer systems that can recognize speech, in improving speech recognition for hearing- and language-impaired listeners, and in foreign-language teaching.

The process of perceiving speech begins at the level of the sound signal and the process of audition. After processing the initial auditory signal, speech sounds are further processed to extract acoustic cues and phonetic information. This speech information can then be used for higher-level language processes, such as word recognition.

One challenging aspect of speech perception is the segmentation problem – we must somehow dissect a continuous speech signal into its component parts (e.g., phonemes, words). A second challenging aspect of speech perception is the lack of invariance problem – sounds are different in different contexts. For example, different people speak differently: speech sounds produced by men have very different frequencies from the sounds that children make, and even the sounds that two same-sex adults produce are quite different (i.e., people have different voices). Similarly, the sound of language spoken in a large auditorium is very different from the sound of language spoken in a laundry room.

Despite these problems, we still correctly identify speech sounds even when they vary dramatically from person to person and context to context. In fact, a child’s /u/ may may be acoustically very much like an adult’s /æ/, but no-one misperceives these sounds.

One might think that we can do this because, despite this variability, speech sounds are characterized by some kind of invariants - i.e., some acoustic property that, for each sound, uniquely identifies it as being that particular sound. That is, there might be some core acoustic property, or properties, that is essential to speech perception. However, despite decades of research, very few invariant properties in the speech signal have been found. As Nygaard and Pisoni (1995) put it:

At first glance, the solution to the problem of how we perceive speech seems deceptively simple. If one could identify stretches of the acoustic waveform that correspond to units of perception, then the path from sound to meaning would be clear. However, this correspondence or mapping has proven extremely difficult to find, even after some forty-five years of research on the problem.

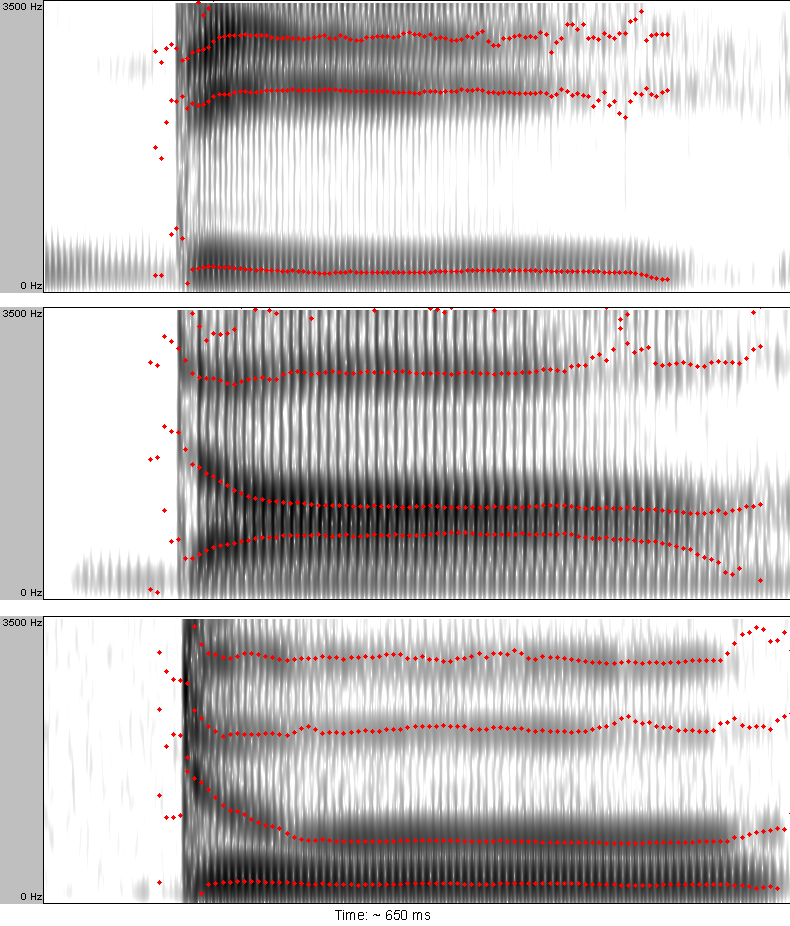

This reflects both a one-to-many and a many-to-one problem. The one-to-many problem is that a particular acoustic aspect of the speech signal can cue multiple different linguistically relevant dimensions. For example, the duration of a vowel in English can indicate whether or not the vowel is stressed, or whether it is in a syllable closed by (~ending with) a voiced or a voiceless consonant, and in some cases (like American English /ɛ/ and /æ/) it can distinguish the identity of vowels (Klatt, 1976). A second reason is the converse, a many-to-one problem: a particular linguistic unit can be cued by several different acoustic properties. For example, the figure below shows how the onset formant transitions of /d/ differ depending on the following vowel but they are all interpreted as the phoneme /d/ by listeners (Liberman, 1957).

Lack of invariance

This lack of acoustic invariants in the speech signal is often referred to as the lack of invariance problem: there appear to be no (or at least few) reliable constant relations between a phoneme and its acoustic manifestation. There are several reasons for this:

Variation due to linguistic context

The surrounding linguistic context influences the realization of a given speech sound, such that speech sounds are influenced by (and become more like) preceding and/or following speech sounds. This is termed coarticulation (i.e., because aspects of different sounds are being articulated concurrently).

Variation due to differing speech conditions

Another important factor that causes variation is differing speech rate. Many phonemic contrasts are constituted by temporal characteristics (short vs. long vowels or consonants, affricates vs. fricatives, plosives vs. glides, voiced vs. voiceless plosives, etc.) and they are certainly affected by changes in speaking tempo.[1] Another major source of variation is articulatory carefulness vs. sloppiness which is typical for connected speech (sometimes referred to as articulatory “undershoot”).

Variation due to different speakers

The resulting acoustic structure of concrete speech productions depends on the physical and psychological properties of individual speakers. For example, men, women, and children generally produce voices having different pitch. Because speakers have vocal tracts of different sizes (due to sex and age especially) the resonant frequencies (formants), which are important for recognition of speech sounds, will vary in their absolute values across individuals (Hillenbrand et al., 1995). Research shows that infants at the age of 7.5 months cannot recognize information presented by speakers of different genders; however by the age of 10.5 months, they can detect the similarities (Houston et al., 2000). Dialect and foreign accent can also cause variation, as can the social characteristics of the speaker and listener (Hay & Drager, 2010).

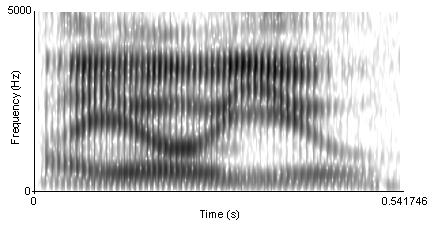

Linearity and the segmentation problem

On top of the lack of invariance of individual speech sounds, we somehow must be able to parse a continuous speech signal into discrete units like phonemes and words. However, although listeners perceive speech as a stream of discrete units (phonemes, syllables, and words), this linearity is difficult to see in the physical speech signal (see the figure below for an example). Speech sounds do not strictly follow one another, rather, they overlap (Fowler, 1995). That is, a speech sound is influenced by the ones that precede and the ones that follow. This influence can even be exerted at a distance of two or more segments (and across syllable- and word-boundaries).

Because the speech signal is not linear, this leads to the segmentation problem. It is difficult to delimit a stretch of speech signal as belonging to a single perceptual unit. Instead, the acoustic properties of phonemes blend together and depend on the context (because, e.g., of coarticulation, discussed above).

Although we still do not know exactly how we overcome the lack of invariance and segmentation problems, we get some help from categorical perception and top-down influences on perception.

Categorical perception

Categorical perception is involved in processes of perceptual differentiation. People perceive (some) speech sounds categorically, that is to say, they are more likely to notice the differences between categories (phonemes) than within categories. The perceptual space between categories is therefore warped, the centers of categories (or “prototypes”) working a bit like magnets for incoming speech sounds (Iverson & Kuhl, 1995).

Put another way, speakers of a given language treat some categories of sounds alike (as belonging to the same phoneme category - thus categorical perception). One consequence of this is that speakers of different languages notice the difference between some phonemes but not others. English speakers can easily differentiate the /r/ phoneme from the /l/ phoneme, and thus rake and lake are heard as different words. In Japanese, however, /r/ and /l/ are variants of the same phoneme, and thus speakers of that language do not automatically categorize the words rake and lake as different words. Try saying the words cool and keep out loud. Can you hear the difference between the two /k/ sounds? To English speakers they both sound the same, but to speakers of Arabic these represent two different phonemes.

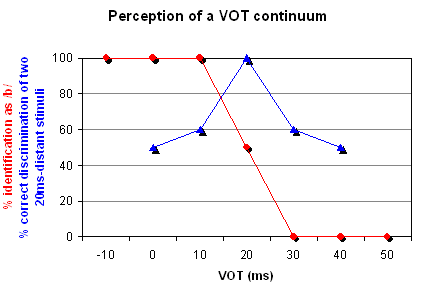

Categorical perception can be demonstrated with an artificial continuum between a voiceless and a voiced bilabial plosive (/p/ vs /b/), where each item on the continuum differs from the preceding one in the amount of voice onset time or VOT. (VOT referes to the length of time between the release of a stop consonant and the start of vibration of the vocal folds). The first sound is a pre-voiced /b/, i.e. it has a negative VOT. Then, increasing the VOT, it reaches zero, i.e. the plosive is a plain unaspirated voiceless /p/. Gradually, adding the same amount of VOT at a time, the plosive is eventually a strongly aspirated voiceless bilabial /pʰ/. In this continuum of, for example, seven sounds, native English listeners will typically identify the first three sounds as /b/ and the last three sounds as /p/ with a clear boundary between the two categories (Lisker & Abramson, 1970). A two-alternative identification (or categorization) test will yield a discontinuous categorization function (see red curve in the Figure above).

In tests of the ability to discriminate between two sounds with varying VOT values but having a constant VOT distance from each other (20 ms for instance), listeners are likely to perform at chance level if both sounds fall within the same category and at nearly 100% level if each sound falls in a different category (see the blue discrimination curve in the Figure above).

The conclusion to make from both the identification and the discrimination test is that listeners will have different sensitivity to the same relative increase in VOT depending on whether or not the boundary between categories was crossed. Similar perceptual adjustment is attested for other acoustic cues as well.

Top-down influences

In a classic experiment, Warren (1970) replaced one phoneme of a word with a cough-like sound. Perceptually, his subjects restored the missing speech sound without any difficulty and could not accurately identify which phoneme had been disturbed, a phenomenon known as the phonemic restoration effect. A related finding from reading research is that accuracy in identifying letters is greater in a word context than when in isolation (the word superiority effect; Reicher, 1969; Wheeler, 1970).

To probe the influence of semantic knowledge on perception, Garnes and Bond (1976) used carrier sentences where target words only differed in a single phoneme (bay/day/gay, for example) whose quality changed along a continuum. When put into different sentences that each naturally led to one interpretation, listeners tended to judge ambiguous words according to the meaning of the whole sentence. That is, higher-level language processes connected with morphology, syntax, or semantics may interact with basic speech perception processes to aid in recognition of speech sounds.

It may be the case that it is not necessary and maybe even not possible for a listener to recognize phonemes before recognizing higher units, like words for example. After obtaining at least a fundamental piece of information about phonemic structure of the perceived entity from the acoustic signal, listeners can compensate for missing or noise-masked phonemes using their knowledge of the spoken language. Compensatory mechanisms might even operate at the sentence level such as in learned songs, phrases and verses, an effect backed-up by neural coding patterns consistent with the missed continuous speech fragments, despite the lack of all relevant bottom-up sensory input (Cervantes Constantino & Simon, 2018).

How Do We Use Language?

Language use is ubiquitous, but how do we actually use it? To be sure, some of us use it to write diaries and poetry, but the primary form of language use is interpersonal. That’s how we learn language, and that’s how we use it. Imagine two men of 30-something age, Adam and Ben, walking down the corridor. Judging from their clothing, they are young businessmen, taking a break from work. They then have this exchange.

Adam: “You know, Gary bought a ring.”

Ben: "Oh yeah? For Mary, isn't it?" (Adam nods.)

If you are watching this scene and hearing their conversation, what can you guess from this? First of all, you’d guess that Gary bought a ring for Mary, whoever Gary and Mary might be. Perhaps you would infer that Gary is getting married to Mary. What else can you guess? Perhaps that Adam and Ben are fairly close colleagues, and both of them know Gary and Mary reasonably well. In other words, you can guess the social relationships surrounding the people who are engaging in the conversation and the people whom they are talking about.

Just like Adam and Ben, we exchange words and utterances to communicate with each other. Let’s consider the simplest case of two people, Adam and Ben, talking with each other. According to Clark (1996), in order for them to carry out a conversation, they must keep track of common ground. Common ground is a set of knowledge that the speaker and listener share and they think, assume, or otherwise take for granted that they share. So, when Adam says, “Gary bought a ring,” he takes for granted that Ben knows the meaning of the words he is using, whom Gary is, and what buying a ring means. When Ben says, “For Mary, isn’t it?” he takes for granted that Adam knows the meaning of these words, who Mary is, and what buying a ring for someone means. All these are part of their common ground.

Note that, when Adam presents the information about Gary’s purchase of a ring, Ben responds by presenting his inference about who the recipient of the ring might be, namely, Mary. In conversational terms, Ben’s utterance acts as evidence for his comprehension of Adam’s utterance—“Yes, I understood that Gary bought a ring”—and Adam’s nod acts as evidence that he now has understood what Ben has said too—“Yes, I understood that you understood that Gary has bought a ring for Mary.” This new information is now added to the initial common ground. Thus, the pair of utterances by Adam and Ben (called an adjacency pair) together with Adam’s affirmative nod jointly completes one proposition, “Gary bought a ring for Mary,” and adds this information to their common ground. This way, common ground changes as we talk, gathering new information that we agree on and have evidence that we share. It evolves as people take turns to assume the roles of speaker and listener, and actively engage in the exchange of meaning.

Common ground helps people coordinate their language use. For instance, when a speaker says something to a listener, he or she takes into account their common ground, that is, what the speaker thinks the listener knows. Adam said what he did because he knew Ben would know who Gary was. He’d have said, “A friend of mine is getting married,” to another colleague who wouldn’t know Gary. This is called audience design (Fussell & Krauss, 1992); speakers design their utterances for their audiences by taking into account the audiences’ knowledge. If their audiences are seen to be knowledgeable about an object (such as Ben about Gary), they tend to use a brief label of the object (i.e., Gary); for a less knowledgeable audience, they use more descriptive words (e.g., “a friend of mine”) to help the audience understand their utterances.

| Coordinating Language Use by Audience Design |

|---|

| An example of a study showing evidence for audience design comes from Isaacs and Clark (1987), who showed that people familiar with New York City could gauge their audience’s familiarity with NYC soon after they begin conversing. Speakers then quickly adjusted their descriptions to help their audience more easily identify landmarks such as the Brooklyn Bridge and Yankee Stadium. More generally, Grice (1975) suggested that speakers typically follow certain rules, which he calls “conversational maxims, by trying to be informative (maxim of quantity), truthful (maxim of quality), relevant (maxim or relation), and clear and unambiguous (maxim of manner). |

So, language use is a cooperative activity, but how do we coordinate our language use in a conversational setting? To be sure, we have a conversation in small groups. The number of people engaging in a conversation at a time is rarely more than four. By some counts (e.g., Dunbar, Duncan, & Nettle, 1995; James, 1953), more than 90 percent of conversations happen in a group of four individuals or less. Certainly, coordinating conversation among four is not as difficult as coordinating conversation among 10. But, even among only four people, if you think about it, everyday conversation is an almost miraculous achievement. We typically have a conversation by rapidly exchanging words and utterances in real time in a noisy environment. Think about your conversation at home in the morning, at a bus stop, in a shopping mall. How can we keep track of our common ground under such circumstances?

Pickering and Garrod (2004) argue that we achieve our conversational coordination by virtue of our ability to interactively align each other’s actions at different levels of language use: lexicon (i.e., words and expressions), syntax (i.e., grammatical rules for arranging words and expressions together), as well as aspects of phonology (i.e., speech rate and accent). For instance, when one person uses a certain expression to refer to an object in a conversation, others tend to use the same expression (e.g., Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986). This occurs for syntactic structures and phonological patterns as well; for example people in conversation tend to converge to similar accents and rates of speech, which are often associated with people’s social identity (Giles, Coupland, & Coupland, 1991). If you have lived in different places where people have somewhat different accents (e.g., United States and United Kingdom), you might have noticed that you speak with Americans with an American accent, but speak with Britons with a British accent.

Pickering and Garrod (2004) suggest that these interpersonal alignments at different levels of language use can activate similar situation models in the minds of those who are engaged in a conversation. Situation models are representations about the topic of a conversation. So, if you are talking about Gary and Mary with your friends, you might have a situation model of Gary giving Mary a ring in your mind. Pickering and Garrod’s theory is that as you describe this situation using language, others in the conversation begin to use similar words and grammar, and many other aspects of language use converge. As you all do so, similar situation models begin to be built in everyone’s mind in part because of alignment at all these other levels of representation. Thus, we use our highly developed interpersonal ability to imitate and cognitive ability to infer (i.e., one idea leading to other ideas) to coordinate our common ground, share situation models, and communicate with each other.

What Do We Talk About?

What are humans doing when we are talking? Surely, we can communicate about mundane things such as what to have for dinner, but also more complex and abstract things such as the meaning of life and death, liberty, equality, and fraternity, and many other philosophical thoughts. Well, when naturally occurring conversations were actually observed (Dunbar, Marriott, & Duncan, 1997), a staggering 60%–70% of everyday conversation, for both men and women, turned out to be gossip—people talk about themselves and others whom they know. Just like Adam and Ben, more often than not, people use language to communicate about their social world.

Gossip may sound trivial and seem to belittle our noble ability for language—surely one of the most remarkable human abilities of all that distinguish us from other animals. Au contraire, some have argued that gossip—activities to think and communicate about our social world—is one of the most critical uses to which language has been put. Dunbar (1996) conjectured that gossiping is the human equivalent of grooming, monkeys and primates attending and tending to each other by cleaning each other’s fur. He argues that it is an act of socializing, signaling the importance of one’s partner. Furthermore, by gossiping, humans can communicate and share their representations about their social world—who their friends and enemies are, what the right thing to do is under what circumstances, and so on. In so doing, they can regulate their social world—making more friends and enlarging one’s own group (often called the ingroup, the group to which one belongs) against other groups (outgroups) that are more likely to be one’s enemies. Dunbar has argued that it is these social effects that have given humans an evolutionary advantage and larger brains, which, in turn, help humans to think more complex and abstract thoughts and, more important, maintain larger ingroups. Dunbar (1993) estimated an equation that predicts average group size of nonhuman primate genera from their average neocortex size (the part of the brain that supports higher order cognition). In line with his social brain hypothesis, Dunbar showed that those primate genera that have larger brains tend to live in larger groups. Furthermore, using the same equation, he was able to estimate the group size that human brains can support, which turned out to be about 150—approximately the size of modern hunter-gatherer communities. Dunbar’s argument is that language, brain, and human group living have co-evolved—language and human sociality are inseparable.

Dunbar’s hypothesis is controversial. Nonetheless, whether or not he is right, our everyday language use often ends up maintaining the existing structure of intergroup relationships. Language use can have implications for how we construe our social world. For one thing, there are subtle cues that people use to convey the extent to which someone’s action is just a special case in a particular context or a pattern that occurs across many contexts and more like a character trait of the person. According to Semin and Fiedler (1988), someone’s action can be described by an action verb that describes a concrete action (e.g., he runs), a state verb that describes the actor’s psychological state (e.g., he likes running), an adjective that describes the actor’s personality (e.g., he is athletic), or a noun that describes the actor’s role (e.g., he is an athlete). Depending on whether a verb or an adjective (or noun) is used, speakers can convey the permanency and stability of an actor’s tendency to act in a certain way—verbs convey particularity, whereas adjectives convey permanency. Intriguingly, people tend to describe positive actions of their ingroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is generous) rather than verbs (e.g., he gave a blind man some change), and negative actions of outgroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is cruel) rather than verbs (e.g., he kicked a dog). Maass, Salvi, Arcuri, and Semin (1989) called this a linguistic intergroup bias, which can produce and reproduce the representation of intergroup relationships by painting a picture favoring the ingroup. That is, ingroup members are typically good, and if they do anything bad, that’s more an exception in special circumstances; in contrast, outgroup members are typically bad, and if they do anything good, that’s more an exception.

| Box: Emotion and Talk |

|---|

| People tend to tell stories that evoke strong emotions (Rimé et al., 1991). Such emotive stories can then spread far and wide through people’s social networks. When a group of 33 psychology students visited a city morgue (an emotive experience for many), they told their experience to about six people on average; each of these people told one person, who in turn told another person on average. By this third retelling of the morgue visit, 991 people had heard about this in their community within 10 days. And this was before online social media platforms. |

In addition, when people exchange their gossip, it can spread through broader social networks. If gossip is transmitted from one person to another, the second person can transmit it to a third person, who then in turn transmits it to a fourth, and so on through a chain of communication. This often happens for emotive stories (see box above). If gossip is repeatedly transmitted and spread, it can reach a large number of people. When stories travel through communication chains, they tend to become conventionalized (i.e., gradually modified fit better into more typical cultural scripts/schemas; Bartlett, 1932). A Native American tale of the “War of the Ghosts” recounts a warrior’s encounter with ghosts traveling in canoes and his involvement with their ghostly battle. He is shot by an arrow but doesn’t die, returning home to tell the tale. After his narration, however, he becomes still, a black thing comes out of his mouth, and he eventually dies. When it was told to a student in England in the 1920s and retold from memory to another person, who, in turn, retold it to another and so on in a communication chain, the mythic tale became a story of a young warrior going to a battlefield, in which canoes became boats, and the black thing that came out of his mouth became simply his spirit (Bartlett, 1932). In other words, information transmitted multiple times was transformed to something that was easily understood by many, that is, information was assimilated into the common ground shared by most people in the linguistic community. More recently, Kashima (2000) conducted a similar experiment using a story that contained a sequence of events that described a young couple’s interaction that included both stereotypical and counter-stereotypical actions (e.g., a man watching sports on TV on Sunday vs. a man vacuuming the house). After the retelling of this story, much of the counter-stereotypical information was dropped, and stereotypical information was more likely to be retained. Because stereotypes are part of the common ground shared by the community, this finding too suggests that conversational retellings are likely to reproduce conventional content.

Language and Thought

What are the psychological consequences of language use? When people use language to describe an experience, their thoughts and feelings can be shaped by the linguistic representation that they have produced rather than the original experience per se (Holtgraves & Kashima, 2008). When we speak a language, we use words as representations of ideas, people, places, and events. The given language that children learn is, of course, connected to their culture and surroundings. But can words themselves shape the way we think about things? Psychologists have long investigated whether language can shape thoughts and actions; a notion called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis or linguistic relativity (Sapir, 1921; Whorf, 1956; Box 3). Early versions of this hypothesis were quite strong, suggesting, for example, that a person whose community language did not have past-tense verbs would be challenged to think about the past (Whorf, 1956). This strong linguistic determinism view has largely been unsupported, however more recent research has debated (sometimes vigorously) more subtle views.

For instance, some linguistic practices, such as pronoun drop, seem to be associated even with cultural values and social institution. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Spanish or Japanese, pronouns can be (and in fact often are) dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., employees having greater loyalty toward their employers) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It may be that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice.

Conclusion

Language and language use constitute a central ingredient of human psychology. Language is an essential tool that enables us to live the kind of life we do. Can you imagine a world in which machines are built, farms are cultivated, and goods and services are transported to our household without language? Is it possible for us to make laws and regulations, negotiate contracts, and enforce agreements and settle disputes without talking? Much of contemporary human civilization wouldn’t have been possible without the human ability to develop and use language. Like the Tower of Babel, language can divide humanity, and yet, the core of humanity includes the ability for language use.

Discussion Questions

- In what sense is language use innate and learned?

- Is language a tool for thought or a tool for communication?

- What sorts of unintended consequences can language use bring to your psychological processes?

Vocabulary

- Audience design

- Constructing utterances to suit the audience’s knowledge.

- Categorical perception

- Perception of acoustic characteristics that vary continuously as distinct phoneme categories

- Coarticulation effects

- How speech sounds are influenced by neighboring speech sounds

- Common ground

- Information that is shared by people who engage in a conversation.

- Ingroup

- Group to which a person belongs.

- Lack of invariance problem

- Lack of acoustic invariants in the speech signal that corresponding to linguistic components

- Lexicon

- Words and expressions.

- Linguistic intergroup bias

- A tendency for people to characterize positive things about their ingroup using more abstract expressions, but negative things about their outgroups using more abstract expressions.

- Morpheme

- The smallest units of meaning in a language

- Outgroup

- Group to which a person does not belong.

- Phoneme

- The smallest unit of sound that makes a meaningful difference in a language

- Priming

- A stimulus presented to a person reminds him or her about other ideas associated with the stimulus.

- Linguistic relativity

- The hypothesis that the language that people use influences the way they think.

- Segmentation problem

- How to dissect a continuous speech signal into linguistically relevant units

- Situation model

- A mental representation of an event, object, or situation constructed at the time of comprehending a linguistic description.

- Social brain hypothesis

- The hypothesis that the human brain has evolved, so that humans can maintain larger ingroups.

- Social networks

- Networks of social relationships among individuals through which information can travel.

- Speech perception

- The process by which the sounds of language are heard, interpreted, and understood.

- Syntax

- Combinatorial “rules” of a language

Image credits

- Marc Wathieu, https://goo.gl/jNSzTC, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8

- I,, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2225868

- Jonas.kluk - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2118459

- Jonas.kluk - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1971718

- Converse College, https://goo.gl/UhbMQH, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8

- aqua.mech, https://goo.gl/Q7Ap4b, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/T4qgSp

References

- Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., & Cleland, A. A. (2000). Syntactic co-ordination in dialogue. Cognition, 75, B13–25.

- Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22, 1–39.

- Cervantes Constantino, F & Simon, JZ (2018). Restoration and Efficiency of the Neural Processing of Continuous Speech Are Promoted by Prior Knowledge. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 12 (56): 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2018.00056

- Dunbar, R. (1996). Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993). Coevolution of neorcortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16, 681–735.

- Dunbar, R. I. M., Duncan, N. D. C., & Nettle, D. (1995). Size and structure of freely forming conversational groups. Human Nature, 6, 67–78.

- Dunbar, R. I. M., Marriott, A., & Duncan, N. D. C. (1997). Human conversational behaviour. Human Nature, 8, 231–246.

- Fowler, C.A. (1995). “Speech production”. In J.L. Miller; P.D. Eimas (eds.). Handbook of Perception and Cognition: Speech, Language, and Communication. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Fussell, S. R., & Krauss, R. M. (1992). Coordination of knowledge in communication: Effects of speakers’ assumptions about what others know. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 378–391.

- Garnes, S., Bond, Z.S. (1976). The relationship between acoustic information and semantic expectation. Phonologica, 285–293.

- Giles, H., Coupland, N., & Coupland, J. (1991) Accommodation theory: Communication, context, and consequence. In H. Giles, J. Coupland, & N. Coupland (Eds.), Contexts of accommodation: Developments in applied sociolinguistics (pp. 1–68). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hay, Jennifer; Drager, Katie (2010). Stuffed toys and speech perception. Linguistics. 48 (4): 865–892.

- Hillenbrand, J., Getty, L.A., Clark, M.J., Wheeler, K. (1995). Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 97 (5 Pt 1): 3099–3111.

- Holtgraves, T. M., & Kashima, Y. (2008). Language, meaning, and social cognition. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 73–94.

- Houston, Derek M.; Juscyk, Peter W. (October 2000). The role of talker-specific information in word segmentation by infants. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 26 (5): 1570–1582.

- Iverson, P., Kuhl, P.K. (1995). Mapping the perceptual magnet effect for speech using signal detection theory and multidimensional scaling. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 97 (1): 553–562.

- James, J. (1953). The distribution of free-forming small group size. American Sociological Review, 18, 569–570.

- Kashima, E., & Kashima, Y. (1998). Culture and language: The case of cultural dimensions and personal pronoun use. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 461–486.

- Kashima, Y. (2000). Maintaining cultural stereotypes in the serial reproduction of narratives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 594–604.

- Kegl, J., Senghas, A., & Coppola, M. (1999). Creation through contact: Sign language emergence and sign language change in Nicaragua. In M. DeGraff (Ed.), Language creation and language change Creolization, diachrony, and development (pp. 179–237). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Klatt, D.H. (1976). Linguistic uses of segmental duration in English: Acoustic and perceptual evidence. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 59 (5): 1208–1221.

- Liberman, A.M. (1957). Some results of research on speech perception. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 29 (1): 117–123

- Lisker, L., Abramson, A.S. (1970). The voicing dimension: Some experiments in comparative phonetics. Proc. 6th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Prague: Academia. pp. 563–567.

- Maass, A., Salvi, D., Arcuri, L., & Semin, G. (1989). Language use in intergroup contexts: The linguistic intergroup bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 981–993.

- Mitchell, R.E. & Young, T.A. (2022). How many people use sign language? A national health survey-based estimate. Working Paper No. DRC2022.2, Gallaudet University.

- Nygaard, L.C., Pisoni, D.B. (1995). “Speech Perception: New Directions in Research and Theory”. In J.L. Miller; P.D. Eimas (eds.). Handbook of Perception and Cognition: Speech, Language, and Communication. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 169–226.

- Reicher, G. M. (1969). Perceptual recognition as a function of meaningfulness of stimulus material. J. Exp. Psychol. 81, 275–280.

- Rimé, B., Mesquita, B., Boca, S., & Philippot, P. (1991). Beyond the emotional event: Six studies on the social sharing of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 5(5-6), 435-465.

- Sapir, E. (1921). Language: An introduction to the study of speech. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace.

- Semin, G., & Fiedler, K. (1988). The cognitive functions of linguistic categories in describing persons: Social cognition and language. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 558–568.

- Warren, R.M. (1970). Restoration of missing speech sounds. Science. 167 (3917): 392–393.

- Wheeler, D. D. (1970). Processes in word recognition. Cogn. Psychol. 1, 59–85.

- Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, thought, and reality (J. B. Carroll, Ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Adapted from

- Kashima, Y. (2021). Language and language use. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology, Rose, M. Spielman, R.M., Jenkins, W.J., & Lovett, M.D. (2020).

- 7.2 Language. In OpenStax:Psychology 2e, and Walinga & Stangor (2010).

- Communicating With Others: The Development and Use of Language. In Introduction to Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition – all CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Speech Perception retrieved 3/25/21, CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Slevc (2021). Speech perception and language use. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.