Language and Brain

Adapted from multiple sources (see below)

Introduction

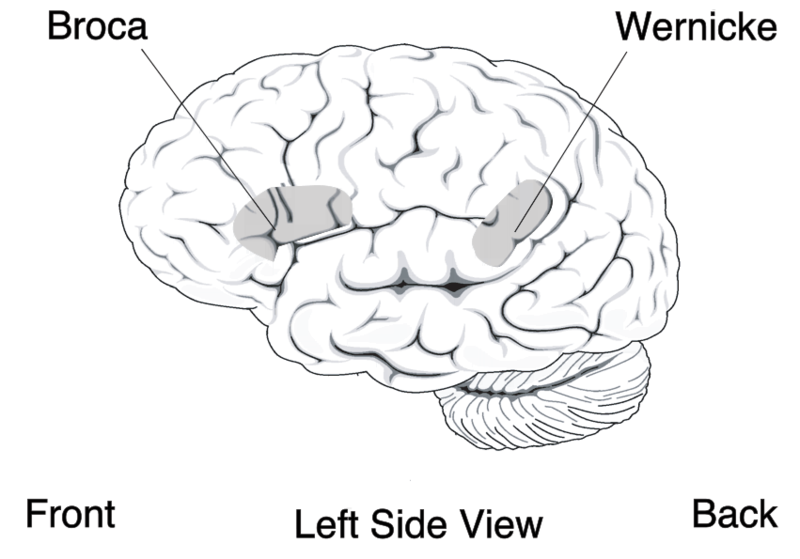

For the 90% of people who are right-handed, language processing relies predominately on the left cerebral cortex, although for some left-handers this pattern is reversed. These differences can easily be seen in the results of neuroimaging studies that show that listening to and producing language creates greater activity in the left hemisphere than in the right. Left frontal regions, including Broca’s area, are involved in language production and syntactic processing. This area was first localized in the 1860s by the French physician Paul Broca, who studied patients with lesions to various parts of the brain. Temporal regions including Wernicke’s area, an area of the brain next to the auditory cortex, is implicated in language comprehension.

Evidence for the importance of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas in language is seen in patients who experience aphasia, a condition in which language functions are severely impaired.

Aphasia

Video credit: National Aphasia Association

Aphasia is an inability to comprehend or formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions. The major causes are a cerebral vascular accident (stroke) or head trauma. Aphasia can also be the result of brain tumors, brain infections, or neurodegenerative diseases, but the latter are far less prevalent (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association).

To be diagnosed with aphasia, a person’s speech or language must be significantly impaired in one (or more) of four aspects of communication following acquired brain injury. Alternately, in the case of progressive aphasia, it must have significantly declined over a short period of time. The four aspects of communication are auditory comprehension, verbal expression, reading and writing, and functional communication.

The difficulties of people with aphasia can range from occasional trouble finding words, to losing the ability to speak, read, or write; intelligence, however, is unaffected. Either or both expressive language and receptive language can be affected. Aphasia also affects visual language such as sign language (Damasio, 1992). Although a prevalent deficit in the aphasias is anomia, which is a difficulty in finding an intended word, the use of formulaic expressions in everyday communication is often preserved (Stahl & Van Lancker Sidtis, 2015). For example, while a person with aphasia, particularly Broca’s aphasia, may not be able to ask a loved one when their birthday is, they may still be able to sing “Happy Birthday”.

Aphasia is not caused by damage to the brain that results in motor or sensory deficits, which produces abnormal speech; that is, aphasia is not related to the mechanics of speech but rather the individual’s language cognition (although a person can have both problems, particularly if they suffered a hemorrhage that damaged a large area of the brain). An individual’s “language” is the socially shared set of rules, as well as the thought processes that go behind verbalized speech. It is not a result of a more peripheral motor or sensory difficulty, such as paralysis affecting the speech muscles or a general hearing impairment.

Aphasia affects about 2 million people in the US and nearly 180,000 people acquire the disorder every year in the US alone (National Aphasia Association). Any person of any age can develop aphasia, given that it is often caused by a traumatic injury. However, people who are middle aged and older are the most likely to acquire aphasia, as the other etiologies are more likely at older ages; for example, strokes, which account for most documented cases of aphasia: about a quarter of people who survive a stroke develop aphasia (Berthier, 2005).

Subtypes of Aphasia

Aphasia is best thought of as a collection of different disorders, rather than a single problem. Each individual with aphasia will present with their own particular combination of language strengths and weaknesses. Consequently, it is a challenge to document the various difficulties that can occur in different people, let alone decide how they might best be treated. Most classifications of the aphasias tend to divide the various symptoms into broad classes. A common approach is to distinguish between the fluent aphasias (where speech remains fluent, but content may be lacking, and the person may have difficulties understanding others), and the nonfluent aphasias (where speech is very halting and effortful, and may consist of just one or two words at a time).

However, no such broad-based grouping has proven fully adequate. There is wide variation among people even within the same broad grouping, and aphasias can be highly selective. For instance, people with naming deficits (anomic aphasia) might show an inability only for naming words from certain categories.

An additional complication is that there are difficulties with speech and language that typically come with normal aging as well. As we age, language can become more difficult to process resulting in a slowing of verbal comprehension, reading abilities and more likely word finding difficulties. With each of these though, unlike some aphasias, functionality within daily life remains intact.

The most common types of aphasia are Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia:

-

Individuals with Broca’s aphasia frequently speak short, meaningful phrases that are produced with great effort. It is thus characterized as a nonfluent aphasia. Affected people often omit function words such as “is”, “and”, and “the”. For example, a person with expressive aphasia may say, “walk dog”, which could mean “I will take the dog for a walk”, “you take the dog for a walk” or even “the dog walked out of the yard”. Individuals with expressive aphasia are able to understand the speech of others to varying degrees. Because of this, they are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated by their speaking problems. While Broca’s aphasia may appear to be solely an issue with language production, evidence suggests that Broca’s aphasia may be rooted in an inability to process syntactic information. Some individuals with Broca’s aphasia have a speech automatism (also called recurring or recurrent utterance. These speech automatisms can be repeated lexical speech automatisms; e.g., modalisations (‘I can’t…, I can’t…’), expletives/swearwords, numbers (‘one two, one two’) or non-lexical utterances made up of repeated, legal but meaningless, consonant-vowel syllables (e.g.., /tan tan/, /bi bi/). In severe cases the individual may be able to utter only the same speech automatism each time they attempt speech. (examples from Code, 1982).

-

Individuals with Wernicke’s aphasia, also referred to as receptive or fluent aphasia, may speak in long sentences that have little or no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even create new words (neologisms). For example, someone with receptive aphasia may say, “delicious taco”, meaning “The dog needs to go out so I will take him for a walk”. They have poor auditory and reading comprehension, and fluent, but nonsensical, oral and written expression. Individuals with receptive aphasia usually have great difficulty understanding the speech of both themselves and others and are, therefore, often unaware of their mistakes. Receptive language deficits usually arise from lesions in the posterior portion of the left hemisphere at or near Wernicke’s area (DeWitt & Rauschecker, 2013).

Various other subtypes exist as well; see, for example, the National Aphasia Association page on Aphasia subtypes

Classical-localizationist approaches

Localizationist approaches aim to classify the aphasias according to their major presenting characteristics and the regions of the brain that most probably gave rise to them (Goodglass, et al., 2001; Kertesz, 2006). Inspired by the early work of nineteenth-century neurologists Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, these approaches identify two major subtypes of aphasia and several more minor subtypes.

Broca’s, or expressive aphasia is typically associated with damage to the anterior portion of the left hemisphere, including Broca’s area. Individuals with Broca’s aphasia often have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg, because the left frontal lobe is also important for body movement, particularly on the right side.

Wernicke’s, or receptive aphasia has been associated with damage to the posterior left temporal cortex, including Wernicke’s area. These individuals usually have no body weakness, because their brain injury is not near the parts of the brain that control movement.

Although localizationist approaches provide a useful way of classifying the different patterns of language difficulty into broad groups, one problem is that a sizable number of individuals do not fit neatly into one category or another (e.g., Ross & Wertz, 2001). Another problem is that the categories, particularly the major ones such as Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia, still remain quite broad. Consequently, even amongst individuals who meet the criteria for classification into a subtype, there can be enormous variability in the types of difficulties they experience.

In addition, while much has been learned from how language deficits can result from brain damage (as well as from other invasive methods such as mapping language function via direct cortical stimulation; see, e.g., Hamberger & Cole, 2011), more recent technologies have allowed for less invasive neuroimaging methods to assess the neural basis of language processing.

Neuroimaging of Language

Where? (fMRI)

The localization of language functions can also be investigated with functional magnetic resonance imaging or functional MRI (fMRI). fMRI measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow (Huettel et al., 2009). This technique relies on the fact that cerebral blood flow and neuronal activation are coupled. When an area of the brain is in use, blood flow to that region also increases (Logothetis et al., 2001).

Many fMRI studies of language rely on the subtraction paradigm, which assumes that specific cognitive processes can be added selectively in different conditions. Any difference in blood flow between these two conditions can then be assumed to reflect the differing cognitive process. For example, if one wanted to study word processing, one might subtract the measured response from a control condition such as nonword processing from the critical condition of word processing; the difference could then be assumed to reflect activity related to processing of words over and above any processing related to visual stimulation, letter recognition, etc. Note, however, that the subtraction paradigm assumes that a cognitive process can be selectively added to a set of active cognitive processes without affecting them. So, following from the previous example, it assumes that, say, letter processing is not affected by word processing (which could be problematic given various top-down influences on language processing).

When? (EEG and ERPs)

Given how quickly language unfolds over time, considerable neuroscientific work on language processing has relied on electroencephalography (EEG), which allows researchers to measure electrical brain activity in real time while participants perform language tasks. This allows for further evidence for models of language that describe the timeline of cognitive processing from sensory perception to meaning interpretation and response production. Much of this work has relied on an approach known as event related potentials (ERP). An event-related potential is the measured brain response that is the direct result of a specific sensory, cognitive, or motor event (Luck, 2005). More formally, it is any stereotyped electrophysiological response to a stimulus. The study of the brain in this way provides a noninvasive means of evaluating brain functioning.

Typically within ERP analysis, the electrical activity of the brain in response to a stimulus is evaluated on a millisecond or smaller scale which allows for sub-conscious mechanisms such as the processing of language to be tracked in order to identify specific components (electrical inflections that are thought to be related to specific cognitive activities) that represent different stages of language processing. ERP components are usually labeled as acronyms with a letter indicating a positive or negative deflection and a number representing the time elapsed (ms) from the presentation of a stimulus differences between conditions tend to occur. One commonly studied ERP components related to language processing is the N400 (a negative-going deflection that peaks around 400 ms after stimulus onset), which has been found to appear when words are presented that are incongruent with what is expected to be presented in the context of a sentence (Kutas & Hillyard, 1980). Another often-studied component is the P600 (a positive-going deflection peaking around 600 ms after stimulus onset), which has been suggested to reflect violations of syntactic expectations (Osterhout & Holcomb, 1992).

Conclusion

Although our understanding of the neural organization of language is still incomplete, it has been significantly informed by evidence from acquired language deficits (especially Aphasia) and from neuroimaging work. These findings implicate largely (but not exclusively) left lateralized functions and also suggest multiple distinct underlying processes (e.g., for semantic and syntactic processing).

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA):- Aphasia. asha.org.

- Berthier, Marcelo L. (2005). Poststroke Aphasia. Drugs & Aging. 22 (2): 163–182.

- Code, C. (1982). Neurolinguistic analysis of recurrent utterances in aphasia. Cortex. 18: 141–152.

- Damasio AR (February 1992). Aphasia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 326 (8): 531–9.

- DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (November 2013). Wernicke’s area revisited: parallel streams and word processing. Brain and Language. 127 (2): 181–91.

- Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E., & Barresi, B. (2001). The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Hamberger, Marla J.; Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Language Organization and Reorganization in Epilepsy. Neuropsychology Review. 21 (3): 240–51

- Huettel, S. A.; Song, A. W.; McCarthy, G. (2009), Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (2 ed.), Massachusetts: Sinauer

- Kertesz, A. (2006). Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

- Kutas, M.; Hillyard, S. A. (1980). Reading senseless sentences: Brain potentials reflect semantic incongruity. Science. 207 (4427): 203–208

- Logothetis, N. K.; Pauls, Jon; Auguth, M.; Trinath, T.; Oeltermann, A. (July 2001). A neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the BOLD signal in fMRI. Nature. 412 (6843): 150–157.

- Luck, Steven J. (2005). An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. MIT Press

- National Aphasia Association - Aphasia Statistics

- Osterhout, L., & Holcomb, P. J. (1992). Event-related brain potentials elicited by syntactic anomaly. Journal of memory and language, 31(6), 785-806.

- Ross K.B.; Wertz R.T. (2001). Type and severity of aphasia during the first seven months poststroke. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 9: 31–53.

- Stahl B, Van Lancker Sidtis D (2015). Tapping into neural resources of communication: formulaic language in aphasia therapy. Frontiers in Psychology. 6 (1526): 1526.

Figures

- Figure from NIH publication 97-4257.

Adapted from:

- Dumper, K., Jenkins, W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perimutter, M. 7.2 Language, CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Walinga & Stangor (2010). Communicating With Others: The Development and Use of Language in Introduction to Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition, CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Wikipedia entries on Aphasia, Event-related potential, and Functional magnetic resonance imaging retrieved 4/2/21, CC-BY-SA 3.0

Slevc (2021). Language and Brain. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.