What is Cognitive Psychology?

Adapted from multiple sources (see below)

Cognitive psychology is the scientific investigation of human cognition, that is, all our mental abilities – perceiving, learning, remembering, thinking, reasoning, and understanding. The term “cognition” stems from the Latin word “cognoscere” – “to know”. Fundamentally, cognitive psychology studies how people acquire and apply knowledge or information. It is closely related to the highly interdisciplinary field of cognitive science and influenced by artificial intelligence, computer science, philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, biology, physics, and neuroscience.

History

Cognitive psychology in its modern form incorporates a remarkable set of new technologies in psychological science. Although published inquiries of human cognition can be traced back at least as far as the ancient Greeks (e.g., Aristotle’s De Memoria in 350 B.C.E; Hothersall, 1984), the intellectual origins of cognitive psychology began with cognitive approaches to psychological problems at the end of the 1800s and early 1900s in the works of Wundt, Cattell, and William James (Boring, 1950).

Cognitive psychology declined in the first half of the 20th century with the rise of “behaviorism” –- the study of laws relating observable behavior to objective, observable stimulus conditions without any recourse to internal mental processes (Watson, 1913; Skinner, 1950). Behaviorism was successful in many ways, in part because focusing on measurable laws of behaviour allowed psychology to transform itself into a more objective scientific field. However, the refusal to consider internal mental processes turned out to be one of behaviorism’s undoings. For example, lack of understanding of the internal mental processes led to no distinction between memory and performance and failed to account for complex learning (Tinklepaugh, 1928; Chomsky, 1959). These issue led to the decline of behaviorism as the dominant branch of scientific psychology and to the “Cognitive Revolution”.

The Cognitive Revolution began in the mid-1950s when researchers in several fields began to develop theories of mind based on complex representations and computational procedures (Miller, 1956; Broadbent, 1958; Chomsky, 1959; Newell et al., 1958). Cognitive psychology became predominant in the 1960s (Tulving, 1962; Sperling, 1960). Ulric Neisser (1967) is typically credited with popularizing the term “Cognitive Psychology” in his 1967 textbook.

Neisser defined cognition as:

…all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used.

Neisser’s definition of cognition remains current in many respects, but is also somewhat limited to a particular information processing view of cognition (discussed later). Neisser had an expansive view of what cognitive research could accomplish, but a somewhat pessimistic take on what it actually has accomplished. Here is another Neisser quote (from “Remembering the Father of Cognitive Psychology,” 2012):

If X is an interesting or socially important aspect of memory, then psychologists have hardly ever studied X.

Neisser’s criticism also remains current: we will encounter examples of research that Neisser might have criticized for being uninteresting or not socially important. And, even though a great deal of research has been conducted, many interesting and socially relevant aspects of cognition remain under investigated. Cognitive Psychology is still very much in-progress.

Assumptions

Cognitive psychology is based on two assumptions:

- Human cognition can at least in principle be fully revealed by the scientific method, that is, individual components of mental processes can be identified and understood.

- Internal mental processes can be described in terms of rules or algorithms in information processing models.

Although these assumptions have been debated (Costall and Still, 1987; Dreyfus, 1979; Searle, 1990), they underlie most cognitive psychological research.

Explanations, Theories, and Models

There is no single agreed-upon format for theories or models in cognition, so explanations take a variety of formats, from informal verbal theories to formal mathematical models (Guest & Martin, 2021; van Rooij, 2022). Explanations can also be aimed at different levels of analysis, and they are often metaphorical in nature.

One of the problems with explaining how cognition works is that cognitive systems – like people and animals – are extremely complex and made up of many interacting physical parts. The complexity makes a reductionist account of cognition very challenging, as there are so many parts to explain. For example, a reductionist theory would seek an explanation of phenomena like human memory in terms of the operation of physiological substrates in the brain, which would require an explanation of how neuronal processes work at an electrical and biological level, which would require explanations in terms of physics and chemistry and so on. Physiological accounts of cognitive phenomena are one standard for reductive explanation, but there are others as well.

Levels of Analysis

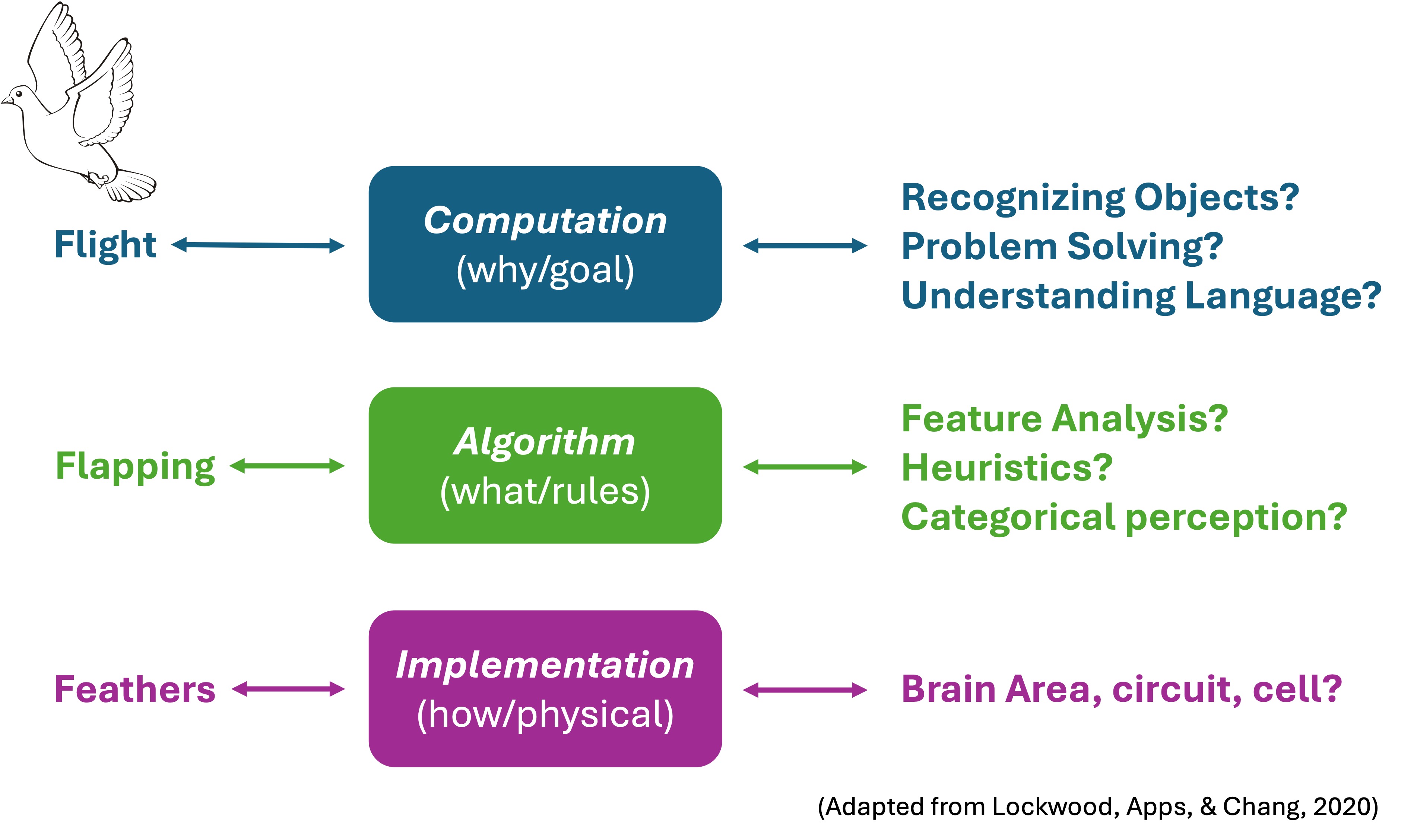

A common approach to explanation in cognition invokes the concept of multiple levels of analysis. For example, vision scientist David Marr described three levels of analysis for the task of explaining visual perception from a computational perspective (Marr, 1982).

Consider first that vision involves a series of transformations beginning at the moment when light hits the retina. From there, photoreceptors in your eyes convert light into electrical impulses sent through the optic nerve, past the optic chiasm, where they are received by neurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus, which is further connected to primary visual areas at the back of the brain. Somehow the visual processing pathways of the brain turn patterns of light falling on the retina into perceptions.

Marr likened visual processing to information processing in a computer system, and suggested that both should be understood in terms of three levels of analysis: computational, representational/algorithmic, and implementational/hardware.

-

Computational Level. The computational level refers to the overall goal of a process. For example, what is the purpose of an eyeball? At this level– and in the context of the rest of the visual system– the goal of eyeballs could be to transduce light photons into electrical signals for further processing. At the computational level it is possible for the goal to be realizable in multiple ways. For example, smartphones with digital cameras also have a lens system to convert photons into electrical signals. So, if you were to imagine yourself as an alien researcher wondering about the purposes of eyeballs or digital camera lens, at the computational level they could have the same goal: to capture and convert light for further processing.

-

Representational or Algorithmic Level. The representational or algorithmic level refers to how a goal is achieved. Take, for instance, making chocolate chip cookies; the recipe’s ingredients and steps are representations and algorithms. Representations are inputs and outputs of the process, such as the raw ingredients that become cookies. The algorithm is a set of instructions for transforming the inputs into the output. A simple recipe for chocolate chips includes a description of the ingredients (representations) and a sequence of steps (algorithm) to process the ingredients into cookies. To return to the domain of vision, photons are the representational inputs to eyeballs and digital cameras. The algorithm in either system refers to the steps or, the way in which, the inputs are transformed into electrical signals as outputs.

-

Hardware implementation level. At the hardware implementation level, we consider how representations and algorithms are physically instantiated and implemented. For instance, what physical elements and processes enable an eye to convert light into electrical signals? Likewise, what physical elements and processes allow a digital camera to capture images and store them in computer memory?

Of course, it would be great to have explanations that span all three levels of analysis, but that’s a tall order! Practically, much can be gained by focusing on a single level of analysis. For example, classical genetics allows us to predict how inherited traits are distributed without an understanding of DNA. More generally, as suggested above, explanations at one level can be “multiply realized” at other levels. That is, there are many potential implementations for a given algorithm and many potential algorithms for a given computational goal. For example, if I have a (computational level) goal to travel to the beach, I can realize that goal algorithmically by driving a car, flying in an airplane, maybe riding a bike, etc. And if I drive, I could realize that algorithm by relying on power stemming from a series of controlled explosions in an internal combustion engine or on power stemming from the conversion of chemical energy to electricity in an electric engine. Thus an explanation at one level of analysis can be (at least somewhat) independent from explanations at other levels.

Approaches

Very much like physics, experiments and simulations/modelling are the major research tools in cognitive psychology. Often, the predictions of the models are directly compared to human behaviour. With the ease of access and wide use of brain imaging techniques, cognitive psychology has seen increasing influence of cognitive neuroscience over the past decade. There are currently three main approaches in cognitive psychology: experimental cognitive psychology, computational cognitive psychology, and neural cognitive psychology (more often called cognitive neuroscience).

Experimental cognitive psychology treats cognitive psychology as one of the natural sciences and applies experimental methods to investigate human cognition. Psychophysical responses, response time, and eye tracking are often measured in experimental cognitive psychology. Computational cognitive psychology develops formal mathematical and computational models of human cognition based on symbolic and subsymbolic representations and dynamical systems. Neural cognitive psychology uses brain imaging (e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI, PET, and Optical Imaging techniques) and neurobiological methods (e.g., study of patients with brain damage) to understand the neural basis of human cognition. The three approaches are often inter-linked and provide both independent and complementary insights in every sub-domain of cognitive psychology.

Sub-domains of Cognitive Psychology

Traditionally, cognitive psychology includes human perception, attention, learning, memory, concept formation, reasoning, judgment and decision-making, problem solving, and language processing. For some, social and cultural factors, emotion, consciousness, animal cognition, and evolutionary approaches have also become part of cognitive psychology.

-

Perception: Those studying perception seek to understand how we construct subjective interpretations of proximal information from the environment. Perceptual systems are composed of separate senses (e.g., visual, auditory, somatosensory) and processing modules (e.g., form, motion; Livingston & Hubel, 1988; Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982; Julesz, 1971) and sub-modules (e.g., Lu & Sperling, 1995) that represent different aspects of the stimulus information. Current research also focuses on how these separate representations and modules interact and are integrated into coherent percepts. Cognitive psychologists have studied these properties empirically with psychophysical methods and brain imaging. Computational models, based on physiological principles, have been developed for many perceptual systems (e.g., Grossberg & Mingolla, 1985; Marr, 1982; Wandell, 1995).

-

Attention: Attention solves the problem of information overload in cognitive processing systems by selecting some information for further processing, or by managing resources applied to several sources of information simultaneously (Broadbent, 1957; Posner, 1980; Treisman, 1969). Empirical investigation of attention has focused on how and why attention improves performance, or how the lack of attention hinders performance (Posner, 1980; Weichselgartner & Sperling, 1987; Chun & Potter, 1995; Pashler, 1999). The theoretical analysis of attention has taken several major approaches to identify the mechanisms of attention: the signal-detection approach (Lu & Dosher, 1998) and the similarity-choice approach (Bundesen, 1990; Logan, 2004). Related effects of biased competition have been studied in single cell recordings in animals (Reynolds, Chelazzi, & Desimone, 1999). Brain imaging studies have documented effects of attention on activation in early visual cortices, and have investigated the networks for attention control (Kanwisher & Wojciulik, 2000).

-

Learning: Learning improves the response of the organism to the environment. Cognitive psychologists study which new information is acquired and the conditions under which it is acquired. The study of learning begins with an analysis of learning phenomena in animals (i.e., habituation, conditioning, and instrumental, contingency, and associative learning) and extends to learning of cognitive or conceptual information by humans (Kandel, 1976; Estes, 1969; Thompson, 1986). Cognitive studies of implicit learning emphasize the largely automatic influence of prior experience on performance, and the nature of procedural knowledge (Roediger, 1990). Studies of conceptual learning emphasize the nature of the processing of incoming information, the role of elaboration, and the nature of the encoded representation (Craik, 2002). Those using computational approaches have investigated the nature of concepts that can be more easily learned, and the rules and algorithms for learning systems (Holland et al., 1986). Those using lesion and imaging studies investigate the role of specific brain systems (e.g., temporal lobe systems) for certain classes of episodic learning, and the role of perceptual systems in implicit learning (Tulving, Gordon Hayman, & MacDonald, 1991; Gabrieli et al., 1995; Grafton, Hazeltine, & Ivry, 1995).

-

Memory: The study of the capacity and fragility of human memory is one of the most developed aspects of cognitive psychology. Memory study focuses on how memories are acquired, stored, and retrieved. Memory domains have been functionally divided into memory for facts, for procedures or skills, and working and short-term memory capacity. The experimental approaches have identified dissociable memory types (e.g., procedural and episodic; Squire & Zola, 1996) or capacity limited processing systems such as short-term or working memory (Cowan, 1995; Dosher, 1999). Computational approaches describe memory as propositional networks, or as holographic or composite representations and retrieval processes (Anderson, 1996, Shiffrin & Steyvers, 1997). Brain imaging and lesion studies identify separable brain regions active during storage or retrieval from distinct processing systems (Gabrieli, 1998).

-

Concept Formation: Concept or category formation refers to the ability to organize the perception and classification of experiences by the construction of functionally relevant categories. The response to a specific stimulus (i.e., a cat) is determined not by the specific instance but by classification into the category and by association of knowledge with that category (Medin & Ross, 1992). The ability to learn concepts has been shown to depend upon the complexity of the category in representational space, and by the relationship of variations among exemplars of concepts to fundamental and accessible dimensions of representation (Ashby, 2000). Certain concepts largely reflect similarity structures, but others may reflect function, or conceptual theories of use (Medin, 1989). Computational models have been developed based on aggregation of instance representations, similarity structures and general recognition models, and by conceptual theories (Barsalou, 2003). Cognitive neuroscience has identified important brain structures for aspects or distinct forms of category formation (Ashby, Alfonso-Reese, Turken, and Waldron, 1998).

-

Judgment and decisions: Human judgment and decision making is ubiquitous – voluntary behavior implicitly or explicitly requires judgment and choice. The historic foundations of choice are based in normative or rational models and optimality rules, beginning with expected utility theory (von Neumann & Morgenstern 1944; Luce, 1959). Extensive analysis has identified widespread failures of rational models due to differential assessment of risks and rewards (Luce and Raiffa, 1989), the distorted assessment of probabilities (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), and the limitations in human information processing (e.g., Russo & Dosher, 1983). Newer computational approaches rely on dynamic systems analyses of judgment and choice (Busemeyer & Johnson, 2004), and Bayesian belief networks that make choices based on multiple criteria (Fenton & Neil, 2001) for more complex situations. The study of decision making has become an active topic in cognitive neuroscience (Bechara, Damasio and Damasio, 2000).

-

Reasoning: Reasoning is the process by which logical arguments are evaluated or constructed. Original investigations of reasoning focused on the extent to which humans correctly applied the philosophically derived rules of inference in deduction (i.e., A implies B; If A then B), and the many ways in which humans fail to appreciate some deductions and falsely conclude others. These were extended to limitations in reasoning with syllogisms or quantifiers (Johnson-Laird, Byne and Schaeken, 1992; Rips and Marcus, 1977). Inductive reasoning, in contrast, develops a hypothesis consistent with a set of observations or reasons by analogy (Holyoak and Thagard, 1995). Often reasoning is affected by heuristic judgments, fallacies, and the representativeness of evidence, and other framing phenomena (Kahneman, Slovic, Tversky, 1982). Computational models have been developed for inference making and analogy (Holyoak and Thagard, 1995), logical reasoning (Rips and Marcus, 1977), and Bayesian reasoning (Sanjana and Tenenbaum, 2003).

-

Problem Solving: The cognitive psychology of problem solving is the study of how humans pursue goal directed behavior. The computational state-space analysis and computer simulation of problem solving of Newell and Simon (1972) and the empirical and heuristic analysis of Wickelgren (1974) together have set the cognitive psychological approach to problem solving. Solving a problem is conceived as finding operations to move from the initial state to a goal state in a problem space using either algorithmic or heuristic solutions. The problem representation is critical in finding solutions (Zhang, 1997). Expertise in knowledge rich domains (i.e., chess) also depends on complex pattern recognition (Gobet & Simon, 1996). Problem solving may engage perception, memory, attention, and executive function, and so many brain areas may be engaged in problem solving tasks, with an emphasis on pre-frontal executive functions.

-

Language Processing: While linguistic approaches focus on the formal structures of languages and language use (Chomsky, 1965), cognitive psychology has focused on language acquisition, language comprehension, language production, and the psychology of reading (Kintsch 1974; Pinker, 1994; Levelt, 1989). Psycholinguistics has studied encoding and lexical access of words, sentence level processes of parsing and representation, and general representations of concepts, gist, inference, and semantic assumptions. Computational models have been developed for all of these levels, including lexical systems, parsing systems, semantic representation systems, and reading aloud (e.g., Seidenberg, 1997; Coltheart et al., 2001; Schank and Abelson, 1977; Massaro, 1998). The neuroscience of language has a long history in the analysis of lesions (Wernicke, 1874; Broca, 1861), and has also been extensively studied with neuroimaging (e.g., Posner et al, 1988).

Applications

Cognitive psychology research has produced an extensive body of principles, representations, and algorithms. Successful applications range from custom-built expert systems to mass-produced software and consumer electronics: (1) Development of computer interfaces that collaborate with users to meet their information needs and operate as intelligent agents, (2) Development of a flexible information infrastructure based on knowledge representation and reasoning methods, (3) Development of smart tools in the financial industry, (4) Development of mobile, intelligent robots that can perform tasks usually reserved for humans, (5) Development of bionic components of the perceptual and cognitive neural system such as cochlear and retinal implants.

However, it is important to realize that cognitive research has not always had uniformly positive implications for society and there are examples where research applications negatively impacted specific groups of people (Prather et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2023). For example, research on mental imagery and the early development of intelligence testing were strongly influenced by the widespread eugenics movement of the time. This era of psychology made a deep impression on subsequent cognitive research, which raises important questions about how psychological research is and should be conducted and applied.

Image credits

- Bob Slevc, CC BY 4.0

- Frits Ahlefeldt, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Modeled from Figure 1 in Lockwood, Apps, & Chang (2020) by Bob Slevc, CC BY 4.0

References

- Anderson, J.R. (1996) The architecture of Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Ashby, F. G. (2000) A stochastic version of general recognition theory. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 44: 310-329.

- Ashby,F. G., Alfonso-Reese, L. A., Turken, A. U., & Waldron, E. M. (1998) A neuropsychological theory of multiple systems in category learning. Psychological Review 105: 442-481.

- Barsalou, L.W. (2003) Abstraction in perceptual symbol systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences 358:.

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H. and Damasio, A. (2000) Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex 10: 295-307.

- Boring, E. G. (1950). A history of experimental psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Broadbent, D. E. (1957) A mechanical model for human attention and immediate memory. Psychological Review 64: 205-215.

- Bundesen, C. (1990) A Theory Of Visual-Attention. Psychological Review 97: 523-547.

- Busemeyer, J. R., & Johnson, J. G. (2004). Computational models of decision making. In D. Koehler & N. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of judgment and decision making (pp. 133–154). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Chomsky, N. (1959) Review of Verbal Behavior, by B.F. Skinner. Language 35: 26-57.

- Chomsky, N. (1965) Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chun, M. M. and Potter, M. C. (1995) A two-stage model for multiple target detection in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance 21: 109-127.

- Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R., & Ziegler, J. (2001) DRC: A Dual Route Cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychological Review , 108, 204 - 256.

- Costall, A. and Still, A. (eds) (1987) Cognitive Psychology in Question. Brighton: Harvester Press Ltd.

- Cowan, N. (1995) Attention and memory: an integrated framework, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Craik, F. I. M. (2002) Levels of processing: Past, present… and future? Memory 10: 305-318.

- Dosher, B.A. (1999) Item interference and time delays in working memory: Immediate serial recall. International Journal of Psychology Special Issue: Short term/working memory, 34: 276-284.

- Dreyfus, H. L. (1979) What computers can’t do: the limits of artificial intelligence, New York : Harper and Row.

- Estes, W. K. (1969) Reinforcement in human learning. In J. Tapp (Ed.), Reinforcement and behavior. New York: Academic Press.

- Fenton, N. and Neil, M. (2001) Making Decisions: using Bayesian nets and MCDA, Knowledge-based Systems 14: 307-325.

- Gabrieli, J. D. E. (1998) Cognitive neuroscience of human memory. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 87-115.

- Gabrieli, J.D.E., Fleischman, D.A., Keane, M.M., Reminger, S.L. and Morrell, F. (1995) Double dissociation between memory systems underlying explicit and implicit memory in the human brain. Psychological Science 6: 76-82.

- Gobet, F. and Simon, H. A. (1996) Recall of random and distorted chess positions: implications for the theory of expertise. Memory & cognition 24: 493-503.

- Grafton, S. T., Hazeltine, E., and Ivry, R. (1995) Functional mapping of sequence learning in normal humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 7: 497–510.

- Grossberg, S. and Mingolla, E. (1985) Neural dynamics of form perception: boundary completion, illusory figures, and neon color spreading. Psychological Review, 92: 173-211.

- Guest, O., & Martin, A. E. (2021). How computational modeling can force theory building in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 789–802.

- Holland, J. H., Holyoak, K. J., Nisbett, R. E., and Thagard, P. R. (1986) Induction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Holyoak, K. J. and Thagard, P. (1995) Mental leaps analogy in creative thought, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hothersall, David (1984) History of Psychology, NY: Random House.

- Johnson-Laird, P. N., Byrne, R. M. J. and Schaeken, W. (1992) Propositional reasoning by model, Psychology Review 99: 418-439.

- Julesz, B. (1971) Foundations of cyclopean perception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 47: 263-292.

- Kahneman, D., Slovic, P. and Tversky, A. (1982) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kandel, E. R. (1976) Cellular basis of behavior: An introduction to behavioural neurobiology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Kanwisher N and Wojciulik E. (2000) Visual attention: Insights from brain imaging. Nature Review Neuroscience 1: 91-100.

- Kintsch, W. (1974) The representation of meaning in memory, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Livingstone, M.S. and Hubel, D.H. (1988) Segregation of form, colour, movement and depth: Anatomy, physiology and perception. Science 240: 740–749.

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1989) Speaking: From Intention to Articulation, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Logan, G.D. (2004) Cumulative progress in formal theories of attention. Annual Review Of Psychology 55: 207-234.

- Lu, Z.-L., & Dosher, B.A. (1998) External noise distinguishes attention mechanisms. Vision Research 38:.

- Lu, Z.-L., & Sperling, G. (1995) The functional architecture of human visual motion perception, Vision Research 35:.

- Luce, D. R. (1959) Individual choice behavior; a theoretical analysis, New York: Wiley.

- Luce, R. D. and Raiffa, H. (1989) Games and decisions : introduction and critical survey. New York: Dover Publications

- Marr, D. (1982) Vision. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Massaro, D. W. (1998) Perceiving talking faces: from speech perception to a behavioral principle, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- McClelland, J. L. and Rumelhart, D. E. (1981) An Interactive Activation Model of Context Effects in Letter Perception: Part 1, Psychological Review 88: 375-407.

- Medlin, D. L. and Ross, B. H. (1992) Cognitive psychology. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Johanovich.

- Medlin, D. L. (1989) Concepts and conceptual structure. American Psychologist 44: 1469–1481.

- Miller, G.A. (1956) The magical number seven, plus or minus two. Psychological Review 63: 81–97.

- Neisser, U (1967) Cognitive psychology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Newell, A., and Simon, H. A. (1972) Human Problem Solving, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., and Simon, H. A. (1958) Elements of a Theory of Human Problem Solving. Psychological Review 23: 342-343.

- Pashler, H. E. (1999) The psychology of attention, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press,

- Pinker, S. (1994) The language instinct, New York: W. Morrow and Co.

- Posner, M.I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 32: 3-25.

- Posner, M. I., Petersen, S. E., Fox, P. T. and Raichle, R. E. (1988) Localization of cognitive operations in the human brain, Science 240:.

- Prather, R. W., Benitez, V. L., Brooks, L. K., Dancy, C. L., Dilworth‐Bart, J., Dutra, N. B., Faison, M. O., Figueroa, M., Holden, L. R., Johnson, C., Medrano, J., Miller‐Cotto, D., Matthews, P. G., Manly, J. J., & Thomas, A. K. (2022). What Can Cognitive Science Do for People? Cognitive Science, 46(6).

- Remembering the Father of Cognitive Psychology. (2012). APS Observer, 25(5).

- Reynolds, J.H., Chelazzi, L., & Desimone, R. (1999). Competitive mechanisms subserve attention in macaque areas V2 and V4. Journal of Neuroscience 19:.

- Rips, L. J., & Marcus, S. L. (1977). Suppositions and the analysis of conditional sentences. In M. A. Just & P. A. Carpenter (Eds.), Cognitive processes in comprehension. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Roediger III, H. L. (2002) Processing approaches to cognition: The impetus from the levels-of-processing framework. Memory 10: 319-332.

- Russo, J. E. & Dosher, B. A. (1983) Strategies for multiattribute binary choice. J Exp Psychology Learning, Memory & Cognition 9: 676-696.

- Sanjana, N. E. & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2003) Bayesian models of inductive generalization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 15: 59-66.

- Schank, R. C. & Abelson, R. P. (1977) Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding : an inquiry into human knowledge structures, Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Searle, J. R. (1990) Is the brain a digital computer APA Presidential Address.

- Seidenberg, M. S. (1997) Language Acquisition and Use: Learning and Applying Probabilistic Constraints. Science 275:.

- Shiffrin, R. M., & Steyvers, M. (1997). A model for recognition memory: REM – retrieving effectively from memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 4: 145-166.

- Skinner, B. F. (1950) Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review 57: 193-216.

- Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs, 74 1-29.

- Squire, L. R., Zola, S. M. (1996) Structure and function of declarative and non-declarative memory systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93:.

- Thomas, A. K., McKinney de Royston, M., & Powell, S. (2023). Color-evasive cognition: The unavoidable impact of scientific racism in the founding of a field. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32, 137-144.

- Thompson, R. F. (1986) The neurobiology of learning and memory. Science 29: 941 – 947.

- Tinklepaugh, O. L. (1928) An experimental study of representative factors in monkeys, Journal of Comparative Psychology 8: 197–236.

- Tobalske, B. W. (2022). Aerodynamics of avian flight. Current Biology, 32(20): R1105 - R1109

- Treisman, A. M. (1969) Strategies and models of selective attention. Psychological Review 76: 282-299.

- Tulving, E. (1962). Subjective organization in free recall of “unrelated” words. Psychological Review 69: 344-354.

- Tulving, E., Gordon Hayman, C. A. and MacDonald, C. A. (1991) Long-lasting perceptual priming and semantic learning in amnesia, A case experiment. Journal of Experimental Psychology 17: 595-617.

- Ungerleider, L.G. and Mishkin, M. (1982) In D.J. Ingle, M.A. Goodale, and R.J.W. Mansfield (Eds.), Analysis of visual behavior. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van Rooij, I. (2022). Psychological models and their distractors. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(3), 127–128.

- von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O. (1944) Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Wandell, B. (1995) Foundations of vision, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Watson, J.B. (1913) Psychology as the behaviorist views it, Psychological Review 20: 158-177.

- Weichselgartner, E. and G. L. U. S. Sperling (1987) Dynamics of automatic and controlled visual attention. Science 238: 778-780.

- Wickelgren, W. A. (1974) How to solve problems. New York: W. H. Freeman.

- Zhang, J. (1997) The nature of external: Representations in problem solving. Cognitive Science 21: 179-217.

Adapted from

- Zhong-Lin Lu and Barbara Anne Dosher (2007). Cognitive psychology. Scholarpedia, 2(8):2769. CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

- Matthew J. C. Crump. (2021). What is Cognition? In Matthew J. C. Crump (Ed.), Instances of Cognition: Questions, Methods, Findings, Explanations, Applications, and Implications. CC BY-SA 4.0