Mental Imagery

Adapted from Matthew J. C. Crump. (2021). Mental Imagery. In Matthew J. C. Crump (Ed.), Instances of Cognition: Questions, Methods, Findings, Explanations, Applications, and Implications. https://crumplab.com/cognition/textbook

Mental imagery is about the subjective experience of being in your own mind, especially while you are in the process of using your imagination. What can you see in your “mind’s eye” when you use your imagination? Can you visualize a picture, scene, or movie in your mind? Can you hear a song in your head? If so, how would you describe the quality of the mental image? Is it vivid and life-like? If not, how would you describe your experience of using your imagination?

Mental imagery: Imagined sensations of any type, including seeing pictures in your mind’s eye, hearing a song in your head, using your inner voice, and others like imagined smell, touch, or sense of space.

Mental imagery is a paradigm example of research in cognitive psychology because it involves experiences that are entirely internal to your own mental processes. Behaviorists like Watson were strongly opposed to research on mental imagery because it could not be directly observed. However mental imagery was an important topic early in the history of psychology and is a significant part of contemporary cognitive psychology as well.

But how do we study a subjective experience like mental imagery?

Characterizing mental imagery

The first step to understanding the phenomenon of mental imagery is (or was) simply to establish the characteristics about imagery. And the first approach to this was simply to think about it and ask people about it.

Answering questions about mental imagery requires establishing facts about the phenomena that we can trust and collectively agree upon. However, the subjective aspects of mental imagery present difficulties for objective measurement. Nevertheless, the literature contains methods and findings relevant to mental imagery phenomena, and because of the subjective nature of the topic some skepticism is required for evaluating the results of the research. We begin with the method of introspection.

Methods of Introspection and Subjective report

The fancy technical term for “thinking about it” in Psychology is the method of introspection, which involves self-reflecting upon or scrutinizing aspects of your own cognition. You may be using introspection to think about your own mental imagery experience right now. If you described what those experiences are like, you would be using the method of subjective report. Methods of subjective report remain common today, often in the form of questionnaires that ask people to make various subjective judgments. Although introspection and subjective report have their limitations, they have successfully informed our understanding of mental imagery. We’ll start with an early example.

Galton’s Statistics of mental imagery

Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911) was a British psychologist who was one of the first to systematically study mental imagery. To quote from his 1880 paper titled, Statistics of mental imagery (Galton, 1880 - freely available from archive.org), Galton set out to:

“define the different degrees of vividness with which different persons have the faculty of recalling familiar scenes under the form of mental pictures, and the peculiarities of the mental visions of different persons.”

Galton’s Method of Subjective Report

Galton devised the “Breakfast table task” involving a series of structured questions about mental imagery, and sent letters to 100 people asking them to reply with answers to his questions, reprinted here (try it yourself!):

| Galton’s Breakfast table task questions: |

|---|

| “Before addressing yourself to any of the Questions on the opposite page, think of some definite object – suppose it is your breakfast-table as you sat down to it this morning – and consider carefully the picture that rises before your mind’s eye. 1. Illumination – Is the image dim or fairly clear? Is its brightness comparable to that of the actual scene? 2. Definition – Are all the objects pretty well defined at the same time, or is the place of sharpest definition at any one moment more contracted than it is in a real scene? 3. Colouring – Are the colours of the china, of the toast, bread-crust, mustard, meat, parsley, or whatever may have been on the table, quite distinct and natural?” |

Galton’s results

Here are some of the answers from “100 men, at least half of whom are distinguished in science or in other fields of intellectual work.” (reprinted from his original manuscript):

| Cases where the faculty is very high |

|---|

| 1. Brilliant, distinct, never blotchy. |

| 2. Quite comparable to the real object. I feel as though I was dazzled, e.g., when recalling the sun to my mental vision. |

| 3. In some instances quite as bright as an actual scene. |

| Cases where the faculty is mediocre |

|---|

| 46. Fairly clear and not incomparable in illumination with that of the real scene, especially when I first catch it. Apt to become fainter when more particularly attended to. |

| 47. Fairly clear, not quite comparable to that of the actual scene. Some objects are more sharply defined than others, the more familiar objects coming more distinctly in my mind. |

| 48. Fairly clear as a general image; details rather misty. |

| Cases where the faculty is at the lowest |

|---|

| 89. Dim and indistinct, yet I can give an account of this morning’s breakfast table; – split herrings, broiled chickens, bacon, rolls, rather light coloured marmalade, faint green plates with stiff pink flowers, the girls’ dresses, &c., &c. I can also tell where all the dishes were, and where the people sat (I was on a visit). But my imagination is seldom pictorial except between sleeping and waking, when I sometimes see rather vivid forms. |

| 90. I am very rarely able to recall any object whatever with any sort of distinctness. Very occasionally an object or image will recall itself, but even then it is more like a generalised image than an individual image. I seem to be almost destitute of visualising power, as under control. |

| 91. My powers are zero. To my consciousness there is almost no association of memory with objective visual impressions. I recollect the breakfast table, but do not see it. |

Galton’s conclusion

Galton’s major conclusion / discovery was that there are considerable individual differences in mental imagery. Some people reported having very strong powers of mental visualization, some people reported having medium abilities, and other people reported having essentially no abilities to visualize anything in their mind’s eye at all.

If we can trust Galton’s results, then the task of explaining mental imagery just got a little bit harder. For example, in addition to explaining how people mentally image things, we also need to explain how some people can do it very well and others can’t do it at all. This is a good example of the increasing complexity that comes along with the research cycle: asking questions uncovers more facts that raise new questions requiring additional explanation.

Limitations with Galton’s method

Galton’s methods were straightforward. He wanted to know how different people experienced mental imagery, so he asked them to think about it and tell him. Although introspection and subjective report were good starting points they also have significant shortcomings. Consider the following limitations: Galton’s participants could have lied about their mental imagery. Their statements could reflect fictional stories rather than facts about mental imagery abilities. The participants may have inaccurately described their own experiences. For example, descriptions could be exaggerated or contain mistaken impressions. People may use different words that suggest larger differences in mental imagery than actually exist.

Establishing facts about mental imagery is difficult because a person’s subjective experience of their own mental imagery is not directly observable by other people. In other domains of inquiry, direct observation can help people quickly establish a set of agreed upon facts. For example, a group of geologists can all look and point at a rock formation, and agree that the rock formation is there, and then proceed to further inspect and measure the rock formation to gather more directly observable facts about it. Galton’s method of subjective report does have some directly observable measurements, such as the words that people used to describe their mental imagery; but, people’s verbal statements are an indirect attempt to communicate an experience, and do not provide an objective lens for other observers to directly view the experience itself.

Obtaining objective facts about subjective experience is undoubtedly a challenge. One way to increase our confidence in scientific facts is to show that they are reproducible. A reproducible finding is one that reliably occurs when an exact or conceptually similar study is repeated by other researchers. So, do Galton’s core claims and findings replicate?

Reproducing Galton’s mental imagery work

Galton conducted his work in the United Kingdom throughout the last half of the 1800s and, like many of his ideas, they spread among psychologists in other countries. At the turn of the century, American psychologists were busy using Galton’s methods and publishing on the mental imagery abilities of college students. In the 1980s, Armstrong (Armstrong Jr, 1894) gave the Breakfast table task to students at Wesleyan University (which, at that time, was a male college). The general pattern of results was similar to what Galton found: The students reported a wide range of mental imagery abilities, including a small proportion of students who were classified as having little to no visual imagery.

In 1902, French (1902) asked students at Vassar college (at that time, a female college) about their mental imagery abilities with a longer mental imagery questionnaire (developed by Titchener, 1905), that was intended to improve upon Galton’s original questions. The results were mostly consistent with prior results, and the Vassar students reported a wide range of different mental imagery abilities. But one finding was not reproduced: All of the 118 students reported at least some mental imagery abilities, and none reported that they had zero mental imagery abilities. This could mean all of the students happened to have mental imagery abilities, or it could call into question the claims that some people do not have mental imagery. Of course, the results could depend on the questionnaire: Galton had 10 questions about mental imagery, Titchener had almost 90 questions that covered imagery for more senses, which potentially gave students more opportunities to claim that they had at least some mental imagery. Perhaps, Galton and Armstrong would have found all of their participants reporting at least a little bit of mental imagery if they had used the more extensive questionnaire by Titchener.

Aphantasia and Hyperphantasia

Let’s skip ahead a century and ask what recent research on mental imagery looks like. In 2010, Zeman and colleagues reported a case of a patient with “imagery generation disorder” (Zeman et al., 2010) that got picked up in the media. Several people who heard about the finding contacted the researchers to let them know that they also did not experience visual imagery. This led Zeman’s research group to begin examining these claims in more detail and in 2015 they did something very similar to what Galton did; namely, ask people questions about the vividness of their mental imagery (Zeman et al., 2015). They used a newer questionnaire developed to assess the vividness of visual imagery (Marks, 1973) and gave it to people who claimed they had no visual imagery. Perhaps not surprisingly, those same people gave answers to the questionnaire that were consistent with their claims that they had no visual imagery. Zeman coined the term aphantasia to describe the condition of having little to no mental imagery.

The media attention to Zeman’s work on aphantasia caused a great of deal of interest across the world. One of the research participants 2015 study created the Aphantasia Network website, which has grown into a large online community for people with aphantasia. By 2020 (Zeman et al., 2020), Zeman’s group had been contacted by 14,000 people who either claimed they had aphantasia, or the opposite – extremely vivid and life-like mental imagery, termed hyperphantasia. Some of the claims are really quite extraordinary. For example, in a 2021 New York Times article (Zimmer, 2021), cognitive neuroscientist Joel Pearson claimed that ‘hyperphantasia could go far beyond just having an active imagination and that “People [with hyperphantasia] watch a movie, and then they can watch it again in their mind, and it’s indistinguishable.”

I can’t accurately replay a whole movie in my head. That is pretty incredible. To me, this claim is so incredible that I wonder if the person was exaggerating their ability a little bit. Although I am skeptical, there is no shortage of people accomplishing astounding, and objectively verifiable feats of cognition. Daniel Tammet is famous for breaking the European record for correctly reciting, from memory, the first 22,514 digits of the number pi. So, if Daniel Tammet can accurately “replay” the digits of pi for five hours, maybe someone else can replay a whole movie in their mind. Again, the role of direct observation comes into play for lending support to an extraordinary claim. The fact that Daniel could say the digits of pi out loud for other observers to hear, under controlled conditions (where those observers could verify he wasn’t cheating somehow), makes it easier to believe that Daniel’s ability is real. Similarly, if there were more direct methods to test claims about extreme differences in mental imagery abilities, this would lend more support to those extraordinary claims.

Taking stock of the facts so far

We have just surveyed a few examples of research into mental imagery abilities. These examples were chosen to highlight some of the challenges with establishing facts about mental imagery, but the larger point is that these challenges apply to the study of many other cognitive abilities as well.

The work we reviewed so far might be best considered as exploratory research – a kind of fact-finding mission. From Galton to Zeman, the questionnaires have been developed to ask “what” questions, rather than “how” questions. And, it is of course useful to establish facts about “what mental imagery is like”, before developing and testing theories about “how mental imagery works”.

What facts about mental imagery can we say have been established by this research? First, we should acknowledge that reasonable people may have different answers to this question. The research we reviewed all used introspection and subjective report methods (questionnaires) to ask people about their own subjective experience of mental imagery. These methods have limitations as we discussed previously: people might be lying, inaccurate, inattentive, unable to describe their own experience, or describe similar experiences differently. And, of course, the quality of the results is limited by the quality of the measurement tool. It is probably fair to say that these kinds of questionnaire data do not provide clear, objective facts about a person’s internal subjective experience of mental imagery. But it is also fair to say that this research has produced some objective facts about how people describe their own mental imagery. Across centuries, and thousands of participants, people consistently claim that mental imagery is real for them, and similar proportions of people consistently claim that they have extremely different kinds of mental imagery abilities. So if you were to make your own questionnaire to ask random people on the street about their mental imagery abilities, what do you think would happen given the existing research we discussed? Most likely, you would find the same kinds of results that Galton did in 1880 and Zeman did in the 2010s.

Some takeaways from this slice of the literature:

- Asking people about their own experience is a useful thing to do, especially when you want to learn something about their subjective experience.

- People make consistent claims about mental imagery, and provide preliminary forms of subjective evidence about features of their own mental imagery.

- There are limitations due to subjective report, and it would be useful to develop alternative tools to measure different aspects of mental imagery in a more objective way.

Theories, explanation and mental imagery

The cognitive sciences is not only concerned with discovering the facts about cognitive abilities like mental imagery, it is also interested in explaining how the abilities work. Explanations can take different forms, and across the textbook we will encounter explanations ranging from (a) relatively simple claims about how something might work to (b) well-developed verbal theories to (c) highly specified computer simulations that propose working algorithms for specific cognitive abilities. Throughout, I encourage you to think about what kind of account would be a satisfying explanation of how a cognitive ability works.

I think I can safely say that as of right now, there is no broadly accepted theory or explanation about how mental imagery works. As we already discussed, there isn’t really great consensus on the features of mental imagery itself, so the absence of a theory isn’t too surprising. However, there has been a great deal of theoretical debate about mental imagery, and this debate provides a really nice example to discuss how theories and explanations are used in cognitive research.

Mental Imagery as explanation

In the previous section, I mentioned that we skipped about a hundred years of research. And there were some general trends in psychology that shaped how researchers asked questions about mental imagery. Some of the general trends correspond to gradual transitions between “schools” of thought in psychology. At the beginning of psychology in the USA, Titchener (1867-1927) developed the “Structuralist” school of thought, and used careful, but subjective, introspection techniques to interrogate and discover individual components of cognition. Behaviorism was another school of thought that favored asking questions that could only be answered with objective measures of behavior. Some “hard-core” behaviorists like B.F. Skinner (1904-1990), claimed that internal processes of the mind were simply outside the boundaries of scientific inquiry, and that psychology should only study observable phenomena like behavior. So, whole topics like mental imagery received less attention by researchers. However, in the 1950s 60s, and 70s, there was a “cognitive revolution” of sorts, and more psychologists returned to asking questions about cognitive abilities, including mental imagery.

When mental imagery returned as a research topic it also came back as a potential explanation of other cognitive abilities. For example, by the 1960s there was already a very large literature on human memory abilities, which was often focused on examining factors that influence how well people can remember verbal stimuli like words. In 1963, Allan Paivio (Paivio, 1963) considered the possibility that mental imagery might be involved in tasks where people attempt to remember words from a list. He suggested that experiencing strong mental imagery when reading a word could make it easier to remember that word later on. Similarly, other words might not be associated with strong mental imagery, and those kinds of words might be harder to remember later on. Paivio also provided some experimental evidence that was consistent with the idea that mental imagery is involved in memory abilities.

Paivio’s concrete versus abstract memory task

Paivio used a standard paired-associate learning task. He ran experiments on elementary school students, and on college students, and found similar results. Here’s what happened if you were a participant in the experiment.

Everyone was given pairs of words to remember for a later memory test. Each pair involved an adjective and a noun, like “Ingenious-Inventor”. Importantly, there were two different kinds of word-pairs, and this was the critical manipulation in the experiment. The manipulation was whether the noun was more concrete or more abstract. Examples of the two kinds of word pairs are presented below:

| Concrete pairs | Abstract Pairs |

|---|---|

| Ingenious-Inventor | Ingenious-Interpretation |

| Technical-Advertisement | Technical-Discourse |

| Massive-Granite | Massive-Rebellion |

| Subtle-Magician | Subtle-Prejudice |

| Profound-Philosopher | Profound-Analysis |

| Rugged-Arctic | Rugged-Locality |

| Shabby-Hermit | Shabby-Client |

| Clumsy-Burglar | Clumsy-Imitation |

| Unpleasant-Bruise | Unpleasant-Scandal |

| Sensitive-Lungs | Sensitive-Tissue |

| Colorful-Maple | Colorful-Scenery |

| Reliable-Luggage | Reliable-Merchandize |

| Expressive-Actress | Expressive-Temperament |

| Amazing-Circus | Amazing-Crusade |

| Noisy-Trumpet | Noisy-Gossip |

| Fashionable-Overcoat | Fashionable-Apparel |

What makes a noun more concrete or abstract? The general idea is that concrete words are more evocative, meaningful, and easier to mentally image than abstract words. For example, hearing or reading the word “Magician” might cause you to think of a colorful magician’s hat, whereas the word “Discourse” might not bring to mind specific mental images. Paivio chose words that he considered more concrete and more abstract when constructing the lists for his experiment.

During the encoding phase, the experimenter read lists of 16 word pairs out loud, with a two second pause in between. Half of the word pairs had a concrete noun, and the other half had an abstract noun. During the memory test, the experimenter read out only the first word from each pair (the adjective), and participants were asked to remember the word it was paired with and write it down. If you heard the word Amazing and you were given the concrete pair, then the correct answer would be to write down Circus. If you were given the abstract pair, then the correct answer would be Crusade.

The question was whether people would have better memory for the concrete nouns compared to the abstract nouns, and this is exactly what Paivio found. In the second experiment, he found that people remembered on average about 4.5 words correctly if they were concrete nouns, but only about 2 words correctly if they were abstract nouns. This is only a difference of 2.5 words, but the result seemed to be consistent across 120 university students, and it suggested that something about the concrete versus abstract quality of these words caused differences in memory performance for the words.

Paivio’s explanations

Paivio entertained different explanations of his results, and the way he related results to explanations is fairly common in cognitive psychology. In the introduction of his paper he referred to new ideas about how memory might work from Miller, Galanter, & Pribram (Miller et al., 1960), who suggested that mental imagery could help people efficiently organize, store, and then later retrieve information in memory. And, he raised the possibility that mental imagery was the reason why participants remembered concrete (more image-able) better than abstract nouns (less image-able). Let’s call this the mental imagery explanation.

However, Paivio actually concluded that the “concept of mediating imagery… may be unnecessary” to explain his results. Instead, de described another possibility that memory performance was being determined by pre-existing associations between the word pairs. For example, some words are more likely to follow other words, and people may have different learned associations between different words. For example, it’s possible that I have a stronger learned association between “Noisy-Trumpet” (which was a concrete pair) than “Noisy-Gossip” (which was an abstract pair). If I was in this experiment and was given the cue word “Noisy”, I might be better able to remember “Trumpet” not because I formed an mental of image of a “Trumpet”, but because “Noisy” was already more strongly associated with “Trumpet” in the first place. Let’s call this the pre-existing association explanation.

The research cycle and theory testing

More interestingly, Paivio ended his paper with a proposal for another experiment that could put these two explanations to the test. This is an instructive example of how the research cycle is used in cognition to refine questions from one experiment to another. A key ingredient is having at least two tentative explanations of the experimental results that make different testable predictions. Paivio’s were the mental imagery explanation and the pre-existing association explanation. The next ingredient is researcher creativity to come up with a new experiment that is capable of putting the predictions to the test.

For example, imagine that there was a drug that immediately turned off everyone’s mental imagery. If mental imagery is responsible for people remembering concrete nouns better than abstract nouns, and if we repeated the experiment but gave people the drug to turn off their mental imagery, then what should happen to memory for the words? According to the mental imagery explanation, the difference in memory performance between concrete and abstract words should disappear. This is because mental imagery would be “turned off”, and would not be able to cause any differences in memory between the words. If there were still differences in memory between the words, this would be good evidence against the mental imagery explanation. (Relatedly, one might expect people with aphantasia to show no advantage for concrete words.)

Paivio didn’t have a magic wand to make mental imagery turn off, so he suggested a different approach, to control for aspects of the pre-existing association explanation. He proposed a new experiment could be repeated with random pairings between adjectives and concrete versus abstract nouns. For example, Noisy-Trumpet isn’t very random because the adjective noisy happens to be meaningful for some trumpets, and there could easily be pre-existing associations between Noisy and Trumpet. However, the influence of pre-existing associations could potentially be eliminated by randomly assigning unrelated adjectives to the nouns. If the advantage for remembering concrete over abstract nouns persisted under these new control conditions, then Paivio would have evidence that pre-existing associations do not explain his findings. And, perhaps the concept of “mediating imagery” would be necessary to explain these influences on memory for words.

Theories of Mental Representation

Before evaluating the kinds of explanations of cognitive abilities we have seen so far, let’s do one more example from the literature. Throughout the 60s and 70s, there were many other studies like Paivio’s that invoked the concept of mental imagery as potentially necessary to explain how people were performing different kinds of tasks. In 1973, Zenon Pylyshyn (1973) published a critique of the emerging mental imagery explanations, and initiated a lengthy debate with Stephen Kosslyn about the form of mental representations. This debate led to a number of experiments attempting to provide evidence in favor and/or against either position.

I will use the terms analog versus propositional to distinguish between the two theoretical ideas about mental representations. The analog representation idea is that perceptual experiences and mental imagery experiences are represented in somewhat similar (analogous) formats. This could imply that perception is involved somehow in mental imagery, and that mental imagery might behave similarly to perception in some circumstances. Sometimes the analog theory is called the “pictorial” theory, in order to evoke the really simple idea that perceiving and imagining an image might rely on closely related mental representations. (Of course, these theories apply to other forms of mental imagery too, e.g., auditory or olfactory or whatever, so “analog” can be more general term.)

Alternatively, the propositional representation assumption is that mental representations are really fundamentally different from our perceptual experiences. A propositional system uses symbols and rules for their combination and recombination to describe mental representations. We’ll see a more concrete example shortly, but propositional systems aren’t too different from using words to describe an image. A paragraph of words to describe an image involves word symbols and rules for putting words together in order. A well-written paragraph can do an OK job of representing a visual scene. And, it is hopefully clear enough that using words to describe an image involves a very different kind of representation than, say, taking a picture of the image. On this view, people don’t actually have pictures in their mind, instead cognitive abilities are controlled by propositional knowledge and representation systems.

The analog and propositional ideas about cognitive representation are two very different takes on the fabric of cognition. Is our cognition running on perception-like representations of our experiences with the world? Or, is our cognition running on abstract propositional codes that are qualitatively different from perception? Do these alternative ideas about mental representation make different predictions? If so, can the predictions be tested with experiments? To answer these questions, let’s look at an experiment using the mental chronometry technique.

Mental Chronometry

In 1978, Stephen Kosslyn and colleagues (Kosslyn et al., 1978) reported some clever experiments on scanning of mental images. Here’s the quick and dirty version. Imagine a map of the USA, now zoom in on New York City and imagine a little black dot hovering over the city. Whenever you are ready, zoom that little black dot all the way over to Los Angeles. How long it did it take you to mentally scan across your mental image of the map? Mental chronometry refers to measuring how long it takes to perform mental operations like scanning a mental image.

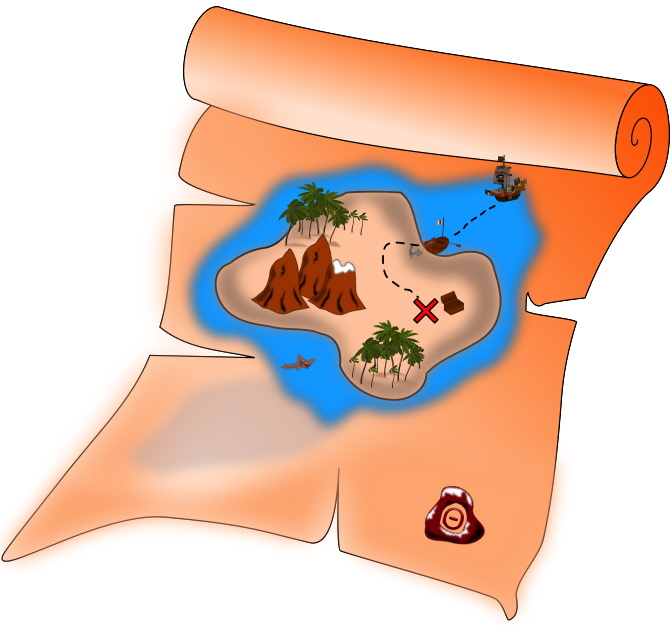

Instead of a map of the USA, participants were shown a map sort of like that in the Figure to the right, and given practice mentally imaging the map and drawing it from memory until they could reproduce it very accurately. The map was taken away and participants were asked to mentally image the map in their mind’s eye. Then, the main task began. On each trial, the participant was asked to focus on one of the depicted locations on their mental image of the map (by imagining a black dot on top of it) and then mentally scan to a different location by moving their imagined black dot to the new location. For example, you might focus on the shark in the water and then scan to the pirate ship (a longer distance); or focus on the mountains and scan to the treasure chest (a shorter distance). Importantly, the researchers measured the time taken to make each scan. The empirical question was whether or not the amount of time to mentally scan from one imagined location to another would depend on the distance between the imagined locations.

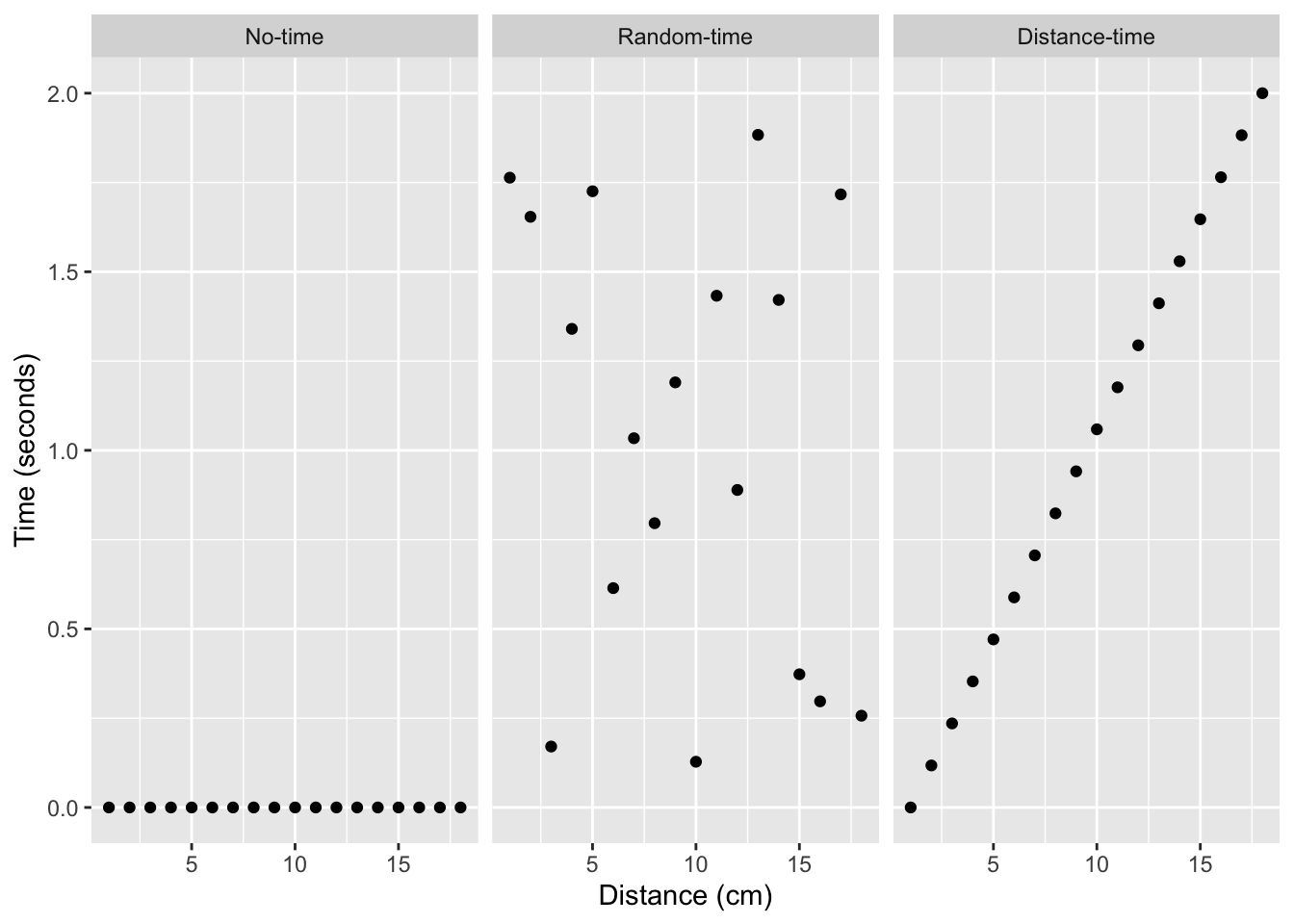

Before we look at the actual data, let’s consider three ways the experiment could have turned out. First, let’s assume that people can scan between different locations immediately without taking any time at all, I will call this the “no-time” hypothesis. Second, let’s assume that people will take some random amount of time to scan between the locations, the “random-time” hypothesis. And third, let’s assume that people’s scanning times will increase with the distance between the imagined locations, the “distance-time” hypothesis. Each of the these hypotheses makes a different prediction about how the results might turn out. Consider the three graphs below, showing how the results could have turned out according to each hypothesis:

Each of the panels shows a scatter plot of possible results. The y-axis (vertical axis) represents amount of time in seconds and ranges from zero to two seconds. Dots that are near the bottom of the plot represent shorter scanning times, and dots closer to the top represent longer scanning times. The x-axis (horizontal axis) represents the distance between locations in centimeters on the real map that participants saw before they had to imagine it. Dots closer to the left of a plot represent scanning times between locations that were close together, and dots closer to the right side represent scanning times between locations that were far apart.

The “no-time” plot shows all of the dots in a line at the bottom, which represents 0 seconds. This is what would happen if people could instantaneously scan from any location to any other location. Even though some locations would be closer together or further apart (represented by the fact that there are dots that go all the way from 1 cm to 15 cm), all of the scanning times would be 0.

The “random-time” plot shows dots spread about randomly. This is what would happen if people do take different amounts of time to scan between locations, but the amount of time would be unpredictable and would not depend on the distance between the imagined locations.

Finally, the “distance-time” plot shows dots in a tilted line (going from the bottom left to the top right) showing a positive relationship or correlation between distance and time. This is what could happen if the distance between imagined locations influences scanning time in a systematic way. Specifically, this graph shows a linear relationship. As the distance between locations increases, so does scanning time. Shorter distances take less time, and longer distances take more time.

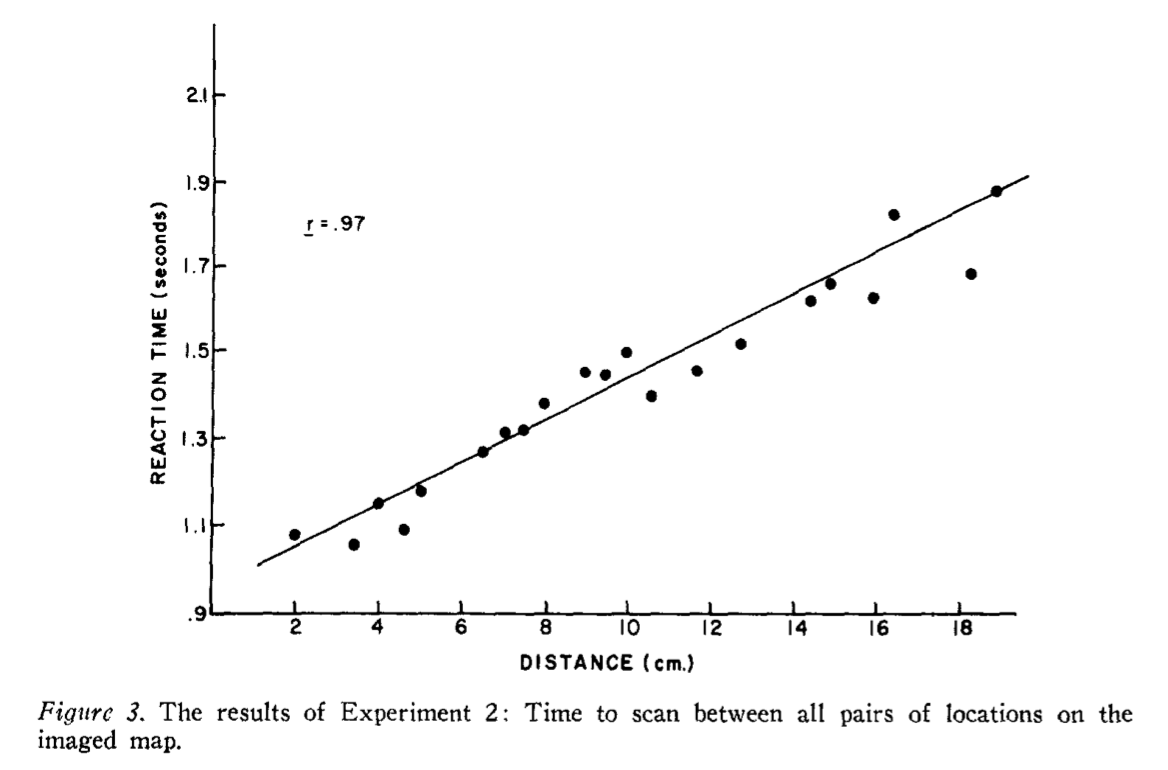

What were the results of the study, and did they look like any of the hypothetical results that we just discussed? The original results are shown below:

The dots represent average scanning times between specific locations for all of the participants, and they mostly fall on the straight line, most similar to the hypothetical “distance-time” results. The data points are a little bit noisy, and they don’t fall precisely on the line every time, so there is a bit of randomness or variability in mental scanning time too. But overall, people appear to take longer to scan between imagined locations on the map as the distance between the locations increases. Interestingly, similar mental scanning results have been found in auditory imagery for songs (e.g., Halpern, 1988).

Before considering what these results could mean for theories of mental representation, let’s note that this study made an attempt at advancing how mental imagery could be investigated using more objective behavioral measures. In this case, the measurement of time to make a mental scan was directly observable. Although directly observable measures of behavior have many desirable properties, including the possibility that multiple observers can mutually confirm and reach consensus on what they are observing, there are also big limitations when it comes to cognition. The biggest limitation is that direct measures of behavior are not direct measures of cognitive processes. The assumption is that cognitive processes are involved in producing the behavior in question, and that measures of behavior therefore indirectly reflect the underlying mechanisms of the mind causing the behavior. So, when someone measures “mental scanning time”, we are only measuring the time associated with whatever happened during “mental scanning”. The measure of time does not directly show whether or not a mental image is like a picture or a proposition. Instead, a common strategy in cognitive research is to theorize about how cognitive processes might work, and attempt to explain how those cognitive processes would result in the observable measures of behavior.

Explaining mental scanning times

Let’s assume that Kosslyn et al’s results can be trusted as a fact, and that when people scan a mental image it really does take longer to scan across longer than shorter distances in the mental image. What does this factoid tell us about the nature of mental representation? Perhaps a better question is, how are factoids like this one used in cognitive research to generate knowledge about cognitive processes?

One strategy involves inventing theories and hypotheses about cognition, and then evaluating whether or not they can predict, anticipate, and/or explain the patterns of measurements found by experiment. If a theory can explain a finding maybe it is correct. If a theory can not explain a finding, maybe it is wrong and should be discarded. Over time the process of theory building and testing would lead to a great many discarded theories that couldn’t explain the findings, and what would be left could be plausible working theories that do a pretty good job explaining the findings. This characterization of how the scientific method incrementally hones in on better explanations connects with issues in the philosophy of science (e.g., Popper, 1959).

Let’s finish this section by returning to the distinction between analog and propositional mental representations, and ask whether the pattern of data is consistent or inconsistent with either of those ideas.

A pictorial explanation of scanning time

Are the findings consistent with the assumption that people have picture-like mental representations of visual images? I don’t think this question can be answered without first speculating more about how analog representations might work, and how they could lead to the results reported by Kosslyn et al. Here’s a simple metaphorical elaboration. I could propose that mental imagery for visual images is like perception for visual scenes, and that because of this relationship, mental imagery should behave in similar ways to visual perception. For example, objects in visual scenes have spatial distances between them, and by analogy mental images of scenes should preserve the spatial distances between imaginary objects. When looking from one object to another in the real world, it can takes time to move your eyes, and the amount of time naturally depends on how far the eyes need to move. If the metaphor holds, it is possible that mentally scanning an image will behave in the same way. So, my answer is yes. The findings could be consistent with the analog mental representation assumption, but only if I created a story that established how this assumption would work.

A propositional explanation of scanning time

Let’s ask whether the results are consistent with the propositional assumption about mental representations. Pylyshyn argued that Kosslyn’s results could be explained without assuming any role for pictorial mental representations. Again, to consider the propositional assumption we need to embed it into a working hypothesis about how people use propositional knowledge. First, consider how propositions could be used to code relations between objects in the scene. I will use sentences as an example of combining abstract symbols (words) to represent relations between objects in the scene.

- The island contains objects

- The rock is on the north end of the island

- The grass is on the north-west side of the island.

- The grass is south-west of the rock

- The tree is south of the grass, in the southwest of the island

- The well is due west of the tree

- The hut is just south of well

- The lake is close to the tree, just to the southeast

The next step is to consider how people might rely on propositions during the mental scanning task. For example, maybe the time to mentally scan between one object and another actually reflects the time it takes to activate knowledge about different objects in the propositional network. Lake and tree are close in the image, but they are also coded together in the same proposition, which could make it easier to go from the lake concept to the tree concept. Similarly, the rock is far from the tree in the image, but the way I wrote the propositions, rock is not directly coded in relation to the tree, but that relation can be established by moving through multiple propositions: the tree is south of the grass, and the grass is south-west of the rock. It might take more time to scan longer distances in the mental image because of the requirement to process multiple propositions.

Society and Historical context

One outgrowth of the mental imagery research we discussed was the creation of the website aphantasia.com, where many people from across the world are creating an online community to discuss and learn more about their own extreme differences in mental imagery abilities. This is a great example of people being interested in how their own cognition works, and wanting learn to more about it. For me personally, I think it would be great if research into mental imagery could help me increase how much control I have over the vividness of my mental imagery. Maybe continued research on this topic will lead to discoveries on this issue. That could be a positive development for me and other people interested in controlling the vividness of their mental imagery.

However, as mentioned before, research into cognitive abilities has not always had uniformly positive implications for society, and there are examples where research applications were severely destructive for some groups of people. For example, remember Sir Francis Galton? In 1880 he published the first study showing evidence for individual differences in mental imagery. Mental imagery is a fascinating topic about how people experience their own mental life. You might assume that Galton was interested in answering questions like, “how does mental imagery work?”. Perhaps this was part of Galton’s motivation for running the study. But, I have purposefully been silent so far about other reasons why Galton ran the study. He tells us the main reason at the beginning of his paper, which reads:

“The larger object of my inquiry is to elicit facts that shall define the natural varieties of mental disposition in the two sexes and in different races, and afford trustworthy data as to the relative frequency with which different faculties are inherited in different degrees.”

Galton was trying to measure differences in mental imagery between people. What was going on at the time that led Galton to ask his questions about mental imagery? How did his results and larger research program influence society? Unfortunately, I should warn you that if you do not already know the answers to these questions, you may find the history disturbing. I know I did.

I mentioned earlier that Galton was in the United Kingdom, and that some of his ideas tended to spread among psychologists in other countries. Galton is famous for many things because he made contributions in many different fields. For example, he is involved with inventing the statistical concept of correlation (Galton, 1889; Stigler, 1989). He was interested in correlation because he was interested in inheritance, especially the idea that children inherit mental abilities from their parents (Galton, 1890). And, Galton was interested in the inheritance of mental abilities because he was also the father of the eugenics movement (Galton, 1865, 1869). Eugenics became a world-wide social movement partly interested in “improving” society across generations through selective human breeding programs.

So one reason Galton was measuring individual differences in mental imagery ability was to aid his eugenics movement. Mental imagery and intelligence were prized traits by Galton. One of his ideas was to create tests, like those that quantified mental imagery ability, that could be used to help classify people into having superior or inferior abilities. The results of the tests could then be used to encourage people with “superior” traits to breed together, and discourage or prevent people with “inferior” traits from breeding together. The eugenics movement thought that breeding humans in this way would produce super humans across generational time. These ideas turned into eugenics programs, promoted scientific racism, and social policies that spread around the the world and caused numerous injustices, human rights violations, and other atrocities.

Most textbooks on cognition (including this one) do not review the historical background and legacy of eugenics in Psychology, perhaps because cognitive psychology and cognitive science only became established academic disciplines after the primary eugenics movements had come and gone. However it is important to realize that the eugenics movement substantially influenced early branches of research into cognitive abilities and shaped the kinds of questions, methods, and social applications of cognitive research (see Crump, 2021, for an approachable OER discussion of this history and its implications for cognitive psychology / cognitive science).

Glossary

- Aphantasia

- A term describing people who report experiencing very little to no mental imagery.

- Hyperphantasia

- A term describing people who report experiencing extremely vivid and life-like mental imagery.

- Introspection

- The process of evaluating one’s own subjective experiences. For example, introspection could involve personally scrutinizing the quality and nature of mental experiences that occur while remembering a previous life event.

- Mental Imagery

- The subjective experience of imagined sensations of any type, including seeing pictures in your mind’s eye, hearing a song in your head, using your inner voice, and others like imagined smell, touch, or sense of space.

References

- Armstrong Jr, A. C. (1894). The imagery of American students. Psychological Review, 1(5), 496. https://doi.org/dkhdx2

- Daniel Tammet. (2021). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Daniel_Tammet&oldid=1027943120

- French, F. C. (1902). Mental imagery of students: A summary of the replies given to Titchener’s questionary by 118 juniors in Vassar college. Psychological Review, 9(1), 40. https://doi.org/cqj438

- Galton, F. (1865). Hereditary talent and character. Macmillan’s Magazine, 12(157-166), 318–327.

- Galton, F. (1869). Hereditary genius. Macmillan.

- Galton, F. (1880). Statistics of Mental Imagery. Mind, 5, 301–318. https://doi.org/gg5vkv

- Galton, F. (1889). I. Co-relations and their measurement, chiefly from anthropometric data. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 45(273-279), 135–145. https://doi.org/dz5sd6

- Galton, F. (1890). Kinship and correlation. The North American Review, 150(401), 419–431.

- Halpern, A.R. (1988). Mental scanning in auditory imagery for songs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14, 434-443.

- Kosslyn, S. M., Ball, T. M., & Reiser, B. J. (1978). Visual images preserve metric spatial information: Evidence from studies of image scanning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 4(1), 47. https://doi.org/c8z6r3

- Marks, D. F. (1973). Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. British Journal of Psychology, 64(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/b6v5wv

- Miller, G. A., Galanter, E., & Pribram, K. H. (1960). Plans and the structure of behavior. Adams-Bannister-Cox.

- Paivio, A. (1963). Learning of adjective-noun paired associates as a function of adjective-noun word order and noun abstractness. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie, 17(4), 370. https://doi.org/d2s523

- Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. (First English Edition) Hutchinson & Co.

- Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1973). What the mind’s eye tells the mind’s brain: A critique of mental imagery. Psychological Bulletin, 80(1), 1. https://doi.org/dbrvzx

- Stigler, S. M. (1989). Francis Galton’s account of the invention of correlation. Statistical Science, 73–79. https://doi.org/dg8nxj

- Titchener, E. B. (1905). Experimental psychology: A manual of laboratory practice (Vol. 2). Johnson Reprint Company.

- Zeman, A. Z., Della Sala, S., Torrens, L. A., Gountouna, V.-E., McGonigle, D. J., & Logie, R. H. (2010). Loss of imagery phenomenology with intact visuo-spatial task performance: A case of “blind imagination.” Neuropsychologia, 48(1), 145–155. https://doi.org/cmfgxv

- Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery - Congenital aphantasia. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 73, 378–380. https://doi.org/gdf5hc

- Zeman, A., Milton, F., Della Sala, S., Dewar, M., Frayling, T., Gaddum, J., Hattersley, A., Heuerman-Williamson, B., Jones, K., & MacKisack, M. (2020). Phantasia–the psychological significance of lifelong visual imagery vividness extremes. Cortex, 130, 426–440. https://doi.org/ghdxvf

- Zimmer, C. (2021, June 8). Many People Have a Vivid “Mind’s Eye,” While Others Have None at All. The New York Times: Science. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/08/science/minds-eye-mental-pictures-psychology.html

Image Credits

- Wikipedia. Public Domain.

- publicdomainvectors.org. Public Domain.

- Crump, 2021. CC BY-SA 4.0

- Kosslyn (1978). Probably copyrighted and I should re-make this image, but omg what a pain.

Adapted from

- Matthew J. C. Crump. (2021). Mental Imagery In Matthew J. C. Crump (Ed.), Instances of Cognition: Questions, Methods, Findings, Explanations, Applications, and Implications. CC BY-SA 4.0

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.